The Sovereign Fox Persuades Law to Dissolve into Politics

The juridical ambitions of Zasha Colah for her edition of the biennale were laudable, but elusive as her symbolic fox.

By Sophie Barfod

The juridical ambitions of Zasha Colah for her edition of the Biennale were laudable, but as elusive as her symbolic fox.

Sophie Barfod • 1/23/25

passing the fugitive on, 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, Berlin, June 14 – September 14, 2025

-

On Site is The Curatorial’s section in which writers review exhibitions from a curatorial perspective—not an art review, a curatorial review. This is also a showcase for master’s degree students in the MA Curatorial Practice program at the School of Visual Arts (the home of the journal) to publish as part of the program—though others are welcome to write for On Site as well.

In this review, Sophie Barfod examines the 13th Berlin Biennale, passing the fugitive on (2025), curated by Zasha Colah, focusing on its use of dramaturgy to frame law, justice, and activism. Structured as a dispersed performance in which viewers are cast as jurors and artworks function as evidence, the Biennale presents law as mutable and performative, gesturing toward fugitivity as an ethical response to lawful violence. Barfod critically evaluates how this approach engages Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL), historical instances of immoral legality, and contemporary artistic practices that destabilize juridical authority, ultimately arguing that the exhibition’s reliance on ambiguity functions as a protective curatorial condition.

Zasha Colah cast her Berlin Biennale, titled passing the fugitive on (June 14–September 14, 2025), as a kind of performance theater spread among four different locations. The drama inherent in using performance theater as a curatorial approach seems an effective attempt to draw in contemporary (often attentionless) art viewers. To that end, the Biennale presented sixty artists and more than one hundred seventy works of art, intending to stimulate a debate on how to position oneself in relation to repressive contexts. Criticism has arisen about the irony of curating a show that apparently seeks justice, while “the viewer is invited to think about almost everywhere but Gaza.”1 It has been argued that the Biennale gravitated toward safer forms of activism, operating within what critics have described as a frame of complicit silence. The Biennale chose to omit geopolitical contexts where global demands for justice continue to be most pressing, therefore aligning itself with sites of political power that prefer such conflicts to remain unspoken.2 This essay examines how justice is articulated curatorially and asks whether legal questions framed through implicit dramaturgy can sustain an activist claim under conditions of political urgency.

Artcom Platform stages a silent monument commemorating the individuals in Kazakhstan who were killed, detained or tortured in 2022 in the uprising known as “Bloody January.” Image: Elisa Carollo.

Colah’s exhibition as a construct operates within the register of the performative, in which passing the fugitive on employs dramaturgy as the primary curatorial intervention. Dramaturgy is traditionally examined curatorially through the ways in which a theatrical setting opposes the standard white cube as a site for display. Even though the Biennale employed scenographic strategies—such as the black-box theater exhibition room at the Hamburger Bahnhof—its staging more generally functioned as a forum for judgment, in which meaning was produced through assigned roles and procedural relations rather than through the white-cube logic of autonomous aesthetic experience.3 Visitors were cast as a public jury, artworks functioned as evidence, and the curatorial framework assumed the position of a closing argument. Such role assignment exceeds metaphor and enters the logic of juridical theater, where interpretation is inseparable from performance. The exhibition space becomes a stage on which judgment is rehearsed rather than resolved. This reveals the risk embedded in this approach: moral interpretation grants judges—and here, viewers—a wide margin for discretion, opening the door to judicial overreach. By asking the audience to “judge the judge,” Colah foregrounds law as a malleable construct, one that is subject to performance and perception. Authority shifts from the institution to the individual, where the viewer becomes the arbiter of moral principles. Some argue that legal interpretation, whether within legal institutions or artistic contexts, is ultimately dependent on collective belief, meaning it is ideological and subject to biases. In the Biennale, Colah seems to shift legal interpretation from legal institutions to aesthetic and social performances, allowing its audience to reflect on their own biases and beliefs in relation to morality.

The Biennale’s central motif is the fugitive fox, a creature that does not break laws but lives indifferently to them. Hence the title, passing the fugitive on: an instruction to carry evidence in body and memory until the right moment to relay it.4 Colah uses the imagery of the fox to pass the idea of fugitivity on to others as an activist gesture and ambition. In the catalogue, she defines this state as the cultural capacity of art to set its own laws in the face of lawful violence, moving outside the law’s demand to be acknowledged. What Colah presents, then, is not merely the fact that law is interpreted, but the possibility of a different horizon for justice, one in which legality gives way to justified resistance and social struggle. Here she converges with the legal movement called Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL), which reframes justice as an ongoing negotiation that takes into account colonial histories, structural asymmetries, and the voices of the marginalized. Critics of TWAIL argue that framing justice as “struggle” or “resistance” risks being too open-ended. If justice is always contested, what are the concrete standards? How do we know when justice is achieved or when resistance itself becomes oppressive?5

The former courthouse on Lehrter Straße, 2025. Image: Raise Galofre.

Colah aims to answer this question with the Biennale’s exhibition section titled “Legality, Illegality, and the Artist’s Claim,” set in the former courthouse on Lehrter Straße. Colah utilizes the site itself as a curatorial argument by excavating the building’s history, as it was the site of the 1916 trial of the German socialist politician and anti-war revolutionary Karl Liebknecht. Prosecuted under wartime censorship laws for his participation in anti-war demonstrations and his criticism of the German military, Liebknecht was a key figure in debate on immoral legality. As the only member of the German parliament to openly oppose the country’s involvement in the First World War, his stance on anti-militarism marked a significant rupture within the legal order.6 Colah mobilizes this legacy by framing the exhibition vis-à-vis this conflict, which was later widely read as unjust. She treats the building less as a neutral container than as an archive of historical institutional immorality. Yet this curatorial precision risks evaporating at the level of encounter. If the historical hinge is legible only in the catalogue, then the exhibition’s ethics remain essentially invisible. For a project that leans on dramaturgy, that’s a structural inconsistency: the trial’s “whispers” should have been staged as part of the exhibition’s script, materialized through some form of scenography or explicit interpretive cues, so that the viewer meets the curatorial argument in space.

Simon Wachmuth’s work plays into this eerie sense of legal injustice with his video commission From Heaven High (2025). In the first half of the work, a black-and-white performance confronts the viewer with the figure of a marching, literally pig-headed soldier at Tempelhofer Feld, where the stark imagery is juxtaposed with Martin Luther’s sacred hymn, “Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her” (From Heaven High I Come). Once repurposed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to support German imperial ambitions, the hymn’s inclusion highlights how cultural symbols have historically been used to sacralize the state and advance nationalist agendas.

Simon Wachsmuth, From Heaven High, 2025, installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, former courthouse on Lehrter Straße, 2025. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025; Zilberman Berlin/Istanbul. Image: Eberle & Eisfeld.

Wachmuth uses this once-sacred hymn to critique the myth of neutrality in cultural heritage, and instead creates a sinister scene concerned with (in)justice. Marching—once a sign of discipline and unity—now becomes a symbol of militarism as performative theater. Wachmuth extends this theatricality into the courtroom that’s shown in the second half of the video, where the logic of militarism is ridiculed further. He presents the scene of a trial as a dramatically lit space in which the very notion of impartiality is replaced by the theatrics of the judge, who declares: “I’ll decide who’s bad and who gets sentenced.” The sovereign tone projects authoritarian overreach, signaling how personal (im)moral judgment, not law, guides decisions. Wachmuth uses this allegory to critique creeping authoritarianism and the erosion of democratic safeguards, hinting at “rule by man, not the law.”7

From Heaven High illustrates the way unlawful directives can issue from the law, calling the very grounding of the law as “blind justice” into question. The work draws on John Heartfield and Rudolf Schlichter’s 1920 Dada installation, Prussian Archangel, at the International Dada Fair in Berlin. It featured a pig-headed papier-mâché soldier with a wire-mesh body hanging from the ceiling, responding to the dubious moral righteousness of military (Prussian) officers in the wake of the disasters of the First World War.8 The original work included an absurd instruction that mirrored the absurdity of war logic, stating that “to fully comprehend this work of art, one should exercise for twelve hours a day on the Tempelhofer Feld with a fully packed backpack and equipped for a field march.” This satirical directive mimics Dada’s anti-war stance, and Wachmuth takes the absurdity of obedience to nationalism as a crude practice at the hands of pigs (sorry, pigs!) and enacts it in his video.

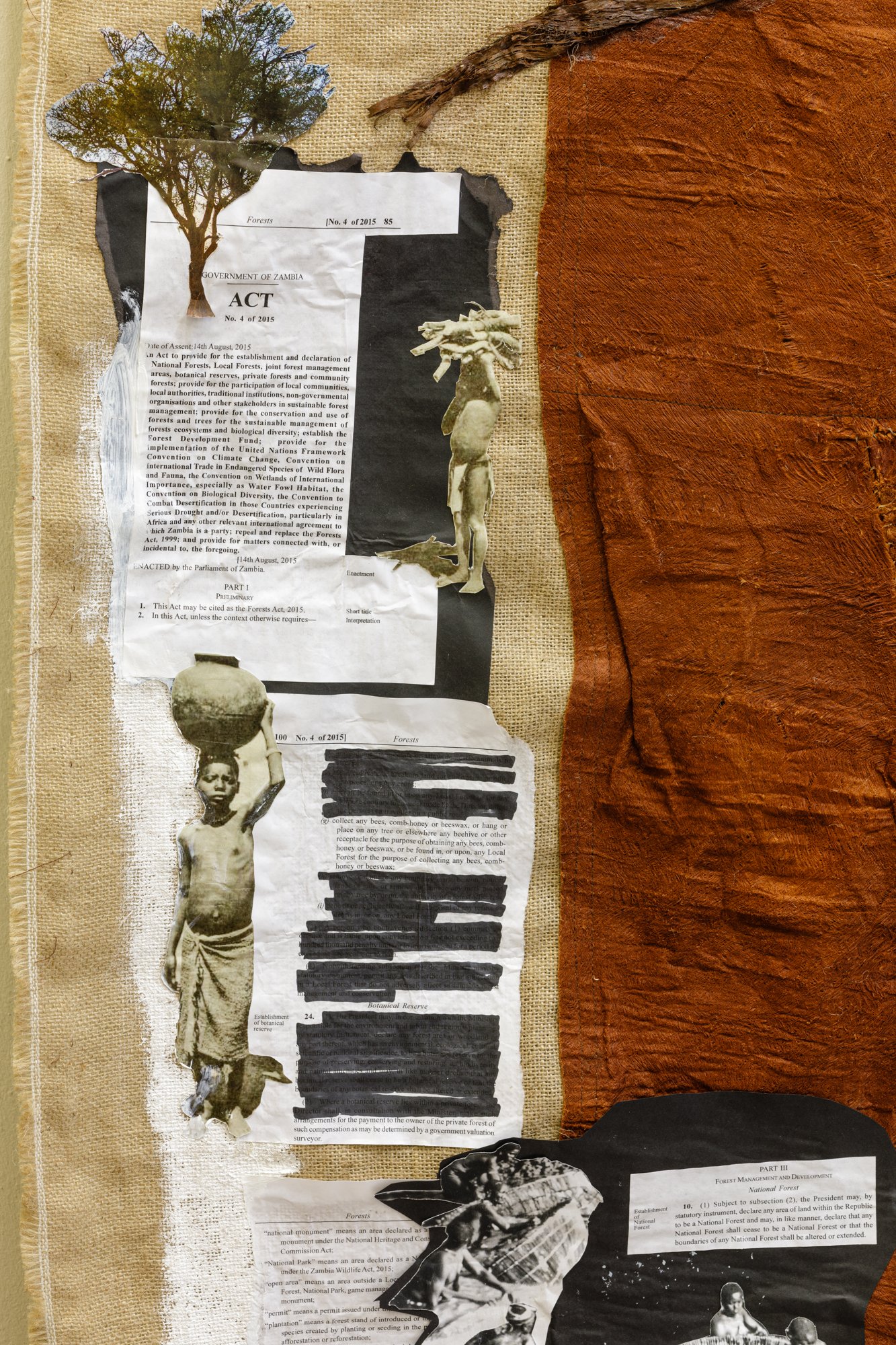

Isaac Kalambata’s collage work Mizyu (2025) seems to be a curatorial illustration of the impact of lawful immorality. Kalambata’s work showcases Zambian legislation on forests and property laws (No. 4 of 2025) with the word “DISPLACED” stamped in red on top of copies of the legislation, illustrating the ways in which the corrupt force of law has brought the displacement of Indigenous populations. The work is accompanied by photographs of what appear to be natives and their belongings. In the center of the piece, we see Mwendanjangula, the “Lord of the Forest,” with his hands tied behind him, eternally attached to a tree. The metaphor touches on the continuous battle between “development” in the eyes of the capitalist beholder and violence in the eyes of the subjugated. Mizyu draws inspiration from the Witchcraft Act of 1914, “a legislation that expressly sought to entrench the colonial Christian church by curtailing alternative spirituality and healing practices within what is now Zambia.” Colah, with the choice of this work, seems to criticize a porous distinction between “this is law” and “this ought to be law.”

Isaac Kalambata, Mizyu, 2025, detail, 13th Berlin Biennale, former courthouse on Lehrter Straße. Courtesy Isaac Kalambata. Image: Eberle & Eisfeld.

One question still lingers after seeing the thirteenth iteration of the Berlin Biennale: if justice is always contested, what are the standards on which it is based and can be counted on in civil societies? Colah’s curatorial approach persuades us to see law as malleable, contingent, and fugitive. TWAIL scholarship affirms this vision, as previously noted, by reframing justice as resistance, as an alternative horizon that refuses colonial hierarchies. In line with the critique that this approach can collapse into ambiguity, the late legal scholar Ronald Dworkin argued that law is always a matter of interpretation, with precedent neither rigid nor random. Yet it must offer integrity and moral validity. In the case of lawful violence, rejecting the law is acting in accordance with a deeper moral logic of the legal system. Essential to this is the discipline of principled interpretation; if everything is up for debate, integrity is lost and law dissolves into politics.9 Between these poles, Colah proposes that the fugitive fox that lives outside of the law, and whose figure suggests that law dissolves into politics, offers neither stability nor certainty. Instead, the fox is a provocation to reimagine the grounds on which justice stands.

Yet the Biennale stops short of articulating what, concretely, should replace that compromised ground. Fugitivity appears as the implied answer—an ethics of refusal, of moving beyond the law’s demand to be acknowledged—but it remains more mood than method. Indeed, the visitor is left with “a sense of a fox with its feet tied.”10 Part of this restraint may be structural rather than accidental: as a publicly funded platform, the Biennale cannot easily stage a critical political position without risking the charge of turning public culture into a partisan mandate.

Colah’s solution is to distribute judgment outward, where the viewers become the jury, and the exhibition provides tools rather than verdicts. But this redistribution produces its own problem. Advocacy requires a legible call and a transmissible ethics—something that can travel beyond the exhibition as more than ambiguity. If fugitivity is meant to be “passed on” as an activist ambition, the dramaturgical conceit promised by the Biennale demanded more than inference; it demands a legible call. Without clearer cues inside the exhibition’s curatorial script, the viewer is left to author the politics alone. In this sense, ambiguity functions as a protective condition. It is even possible that this suspension of principled interpretation was intentional. The Biennale’s reliance on ambiguity seems a wager for the consequences of advocacy to remain hidden, echoing the logic of the fox that survives by remaining elusive, but in doing so cannot be passed on.

Daniel Gustav Cramer, Fox & Coyote, 2024/25. Image: © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2025. Courtesy Sies + Höke, SpazioA, Vera Cortes, Yvon Lambert.

NOTES

1. Martin Herbert, “13th Berlin Biennale Review: What Doesn’t the Fox Say,” ArtReview, September 5, 2025, https://artreview.com/13th-berlin-biennale-for-contemporary-art-various-venues-berlin-review-martin-herbert/.

2. Andrea Scrima, “The Berlin Biennale’s Complicit Silence,” Hyperallergic, July 30, 2025, https://hyperallergic.com/berlin-biennale-complicit-silence/.

3. Colah’s iteration of the Berlin Biennale included four venues. The largest part of the exhibition took place at KW Institute for Contemporary Art. The other venues were the Hamburger Bahnhof–National Gallery for Contemporary Art, Sophiensæle, and the former courthouse on Lehrter Straße.

4. Zasha Colah and Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, eds., 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art: catalogue. (Berlin: Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, 2025).

5. Naz K. Modirzadeh, “‘Let Us All Agree to Die a Little:’ TWAIL’s Unfulfilled Promise,” Harvard International Law Journal 65, no. 1 (Winter 2024): 25–68.

6. John Simkin, “Karl Liebknecht,” Spartacus Educational, updated January 2020, https://spartacus-educational.com/GERliebknecht.htm.

7. Editor’s Note: In this regard, it is worth noting that when The New York Times asked President Donald Trump if there were any limits on his global powers, he replied: “Yeah, there is one thing. My own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me.” https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/08/us/politics/trump-interview-power-morality.html.

8. Simon Wachmuth, From Heaven High (2025). Wall label, 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, former courthouse on Lehrter Straße, Berlin.

9. Ronald Dworkin, Law’s Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986).

10. Herbert, “13th Berlin Biennale Review.”

-

Sophie Barfod is an independent curator from Amsterdam, the Netherlands. She works at the intersection of curating and strategy, currently contributing to W.A.G.E. and SaveArtSpace. Her practice is focused on curating in found spaces, with exhibition concepts often rooted in feminist theory and social practice work. She is currently a student in the MA Curatorial Practice program at the School of Visual Arts, with a Bachelor’s degree (honors) in Politics, Psychology, Law, and Economics from the University of Amsterdam. She has held positions at YAG (McKinsey partner), Heineken, Julietta Alvarez Galeria, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, and is an ex-founder of an experimental arts and technology startup in Amsterdam.

Not Foreign Enough: Revisiting the 2024 Venice Biennale

A year after the Biennale’s latest edition, the philosophical and curatorial questions of Otherness and difference implicit in Artistic Director Adriano Pedrosa’s title, Foreigners Everywhere, feel all the more pressing to address.

By Abbas A Malakar

A year after the Biennale’s latest edition, the philosophical and curatorial questions of Otherness and difference implicit in Artistic Director Adriano Pedrosa’s title, Foreigners Everywhere, feel all the more pressing to address.

Abbas A Malakar • 8/1/25

60th Venice Biennale Arte, Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere, April–November 2024

-

On Site is The Curatorial’s section in which writers review exhibitions from a curatorial perspective—not an art review, a curatorial review. This is also a showcase for master’s degree students in the MA Curatorial Practice program at the School of Visual Arts (the home of the journal) to publish as part of the program—though others are welcome to write for On Site as well.

In this review, Abbas A Malakar reflects on the breadth and depth of the sixtieth edition of the Venice Biennale, curated by Adriano Pedrosa. While Malakar found excellence and range in the historical and geographical selection of works, the problematic categorization of the works and their homogenizing display never accomplished a truly nuanced examination of Otherness that the curator promised. Nonetheless, the issues of difference and tolerance invoked by Pedrosa are all the more urgent in a global political climate of authoritarianism and brute nationalism that we face today.

At the 2024 Venice Biennale’s Central Pavilion entrance. Image courtesy Gabriela Valentin Cruz.

It has been a little more than a year since April 20, 2024, when the 60th Venice Biennale opened its many doors. Venice can be overwhelming. The Biennale can add to that effect. Cut off from the rest of the world, surrounded by history crumbling and drowning, one’s ability to feel can be heightened. Running from pavilion to pavilion, and then trying to cover both the locations at the Giardini and the Arsenale, so many emotions are bound to erupt, and intensely so. As such, both appreciation and criticism of the Biennale can, justifiably, reach extremes. A retrospective thinking, removed from the immediacy of those emotions, hopes to be more objective.

Under the curatorial leadership of Adriano Pedrosa, the artistic director of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo, he gave his Biennale the title Foreigners Everywhere. The aim, according to the Biennale’s official website, was to highlight artists who had historically been excluded from the West. The criteria specifically noted those who had never been shown in Venice, referred to by Pedrosa as “the invisible.”1 In this sense, the exhibition projected hope not only for the world of art but for the people of the Global South.

Pedrosa was, to a degree, celebrated by the media prior to the Biennale’s opening.2 The interviews he gave and the way he spoke of his presence as queer and Brazilian seemed to suggest that he thought these an achievement in themselves, as if he might have accepted laurels before the race even began.3 It should be seen as a success that the decolonial forces of the world led to someone like Pedrosa being given such a role. But this was not an award; it was a job, and that job was not executed very well.

Ibrahim El-Salahi, The Last Sound, 1964, Oil on canvas, 47.8 × 47.8 inches. Image courtesy Venice Biennale.

Before I say more critically, though, Pedrosa should be lauded for his exceptionally keen eye. Credit is due to him for both his choice of artists and their works. He chose incredible works across a vast temporal and geographical spectrum: from Bona De Mandiargues (Rome, Italy, 1926–2000, Paris, France) to Horacio Torres (Livorno, Italy, 1924–1976, New York, US); from Iván Argote (Bogotà, Colombia, 1983–lives in Paris, France) to Pablo Delano (San Juan, Puerto Rico 1954–lives in West Hartford, United States); from Semiha Berksoy (Istanbul, Türkiye, 1910–2004) to Ibrahim El-Salahi (Omdurman, Sudan, 1930–lives in Oxford, UK). It was clear that he engaged in a broad range of research and devised a meticulous system of selection, as one would expect for the Biennale, but true to his vision of inclusivity.

Isaac Chong Wai, Falling Reverseley, 2021–2024, variable dimensions. Image courtesy Isaac Chong Wai.

The primary categories of inclusion, in keeping with the announcement of his own identity, were queer, outsider, foreign, distant, and Indigenous. There was also an emphasis on the “uncanny” and the “strange,” adding two more possible categories.4 His curatorial approach inherently included the frame of Otherness that, of course, truly anyone might feel.5 Thankfully, these broad categories, which in themselves are too abstract to be more than sociological boxes to check off, took on a far more concrete character in the works themselves. This was evident in the Chinese artist Isaac Chong Wai’s explicitly queer and monumental performance video installations; the polyester and stainless-steel installation by Bridget Reweti, Erena Baker, Sarah Hudson, and Terri Te Tau of the Mataaho Collective from New Zealand; and the expansive drawings of the self-taught UK-based Madge Gill, populated by hundreds of people and an array of semi-abstract architectural settings. Let alone the multitudinous works from the Global South that offered a vast range of expressions that were more interesting for their differences than for the homogenizing mantle of Otherness, of the “outsider,” as put forward by Pedrosa.

A display of historical abstract works in the Central Pavilion, though full of excellent pieces, indicated no apparent interest in distinctions of cultural origin and how such differences influenced the creation of the works. Image courtesy Haupt & Binder, Universes in Universe.

The inclination toward categorical abstraction that struggles against the particularity of the works on view, then, is a characteristic problem of this Biennale, and in more ways than one. For example, it figured as an organizing principle of the art curated in one of the large galleries of the Central Pavilion that highlighted Pedrosa’s engagement with historical art. Like Otherness, abstraction in art is not one thing; it did not grow from the same seeds across the world. Yet he ended up disregarding all nuances within the various worlds of abstraction to put together a salon-style arrangement of paintings that reduced the local origins and meaning of each across the spectrum. While Ben Davis, in Artnet News, points out that the selection of artists in this section was “wildly unbalanced geographically,” inclusion could never have been complete—and that was not the primary problem here.6 What should have been a principal concern is the effect that the selected works had when hung as they were—and could have had if the effect had been more thoughtfully considered.

Syed Haider Raza, Offrande, 1986, Acrylic on canvas, 39.4 x 39.4 inches. Image courtesy Venice Biennale.

The selection included artists such as Etel Adnan (Lebanon 1925–2021, France), Carmen Herrera (Cuba 1915–2022, US), and Tomie Ohtake (Japan 1912–2015, Brazil)—all brilliant in their own right, having cross-cultural significance and influence. While the range of great artists from around the world was impressive, it was far less so to make their works appear as a homogenized mass. Consider Sayed Haider Raza (1922–2016), one of the greatest painters in twentieth–century India. Inspired by Indian philosophy and Western modes of expression, his geometric abstractions have influenced generations of artists and have continued to be a beacon for those alive today. Given his role in shaping modernity in India and his presence in the global market, his importance is profound. One had to look at his paintings in between glimpses of two other selected abstract paintings, by Freddy Rodriguez (Dominican Republic 1945–2022, US) and Kazuya Sakai (Argentina 1925–2001, US). Between Sakai’s unique visual language of simple shapes in bright contrast and harmonious synthesis, and Rodriguez’s warmer gestural dynamism in a heavier-toned palette, there was hardly the space and time to consider the deep philosophical foundations of Raza’s art, reducing everything to simple juxtapositions of color and form. As Jackson Arn noted in The New Yorker, none of the abstract works, given the number present in that one room, were presented appropriately to engage viewers enough to “bloom in the beholder’s eye.”7

Kazuya Sakai, Pintura No.9, 1969, acrylic on canvas, 51.2 × 51.2 inches. Image courtesy Venice Biennale

In fact, the entire remit of making “the invisible” visible collapses here; the “rebalancing of the art canon toward the Global South” never amplifying meaning, only multiplying an inventory of superficially arranged works. Perhaps it created a new list of names to drop in the parlance of the market. Other than that, the “foreign” gained no sustainable foothold in accommodating a more substantial cultural equity—a deeper sense of Othering, and with it, the beneficence of greater understanding and tolerance.

Dean Sameshima, Anonymous Faggots, 2024. Image Courtesy Gabriela Valentín Cruz.

The Western world has tried many times to make the Global South a more apparent presence in its discourses, and according to Maximilíano Durón, the Biennale’s promise was rooted in the “condemnation of much of our current situation” in a fight against “right-wing governments around the world that seek to strip women, queer people, and immigrants of their rights.”8 A year later, it does seem that Pedrosa’s intention is recognizable in retrospect, yet it comes at the cost of appropriating the gaze that has historically manufactured Otherness in the colonial system from a position of elevated access and power, rendering the grand gesture of acknowledgment empty in its promise.9

At another of the art world’s monumental exhibitions, documenta 11 staged twenty-three years ago, Okwui Enwezor made history by denying the Western idea of the foreigner as exotic, holding symposia around the world in advance, and arguing for precisely a counter-colonialist reorientation of both art history and the market. Though the market managed its usual tentacular capitalist hypnotism, that documenta did not exoticize.

And so, the problem was not with the intention, but with the unfounded confidence that it could be achieved without producing much more explicit knowledge as the foundation for the works presented. Without that fundamental reframing, as Davis remarked, Pedrosa’s inclusiveness could be seen as “just switching gears from superficial dismissal to superficial celebration.”10 His nationality, the color of his skin, his gender, or sexual orientation didn’t matter (and shouldn’t matter) because his work turned toward the enjoyment of a moneyed global public already inclined to broaden its tastes for novelty, inventory, or true cultural enlightenment.

The idea seemed to be that everyone—whether artist or visitor—fell within the classifications of Outsider, no matter who they were or where they were from. This was an exceptional claim on the part of the curator, who wrote that everyone, deep inside, is somehow always alien to their surroundings. It was surely a noble effort to highlight the socially imposed categories that separate some of us, but, of course, the principal shortcoming of any such claim is that it aims to unite a set of unique experiences under a set of general rubrics—as though these disjointed categories in the end are somehow all the same. On the other hand, in a world that is steeped in violence over the contested rights of land, home, and geographical anchors to identity—whether between Israel/Palestine, Russia/Ukraine, or India/Pakistan—such a show rips into the absurdity of the absolute and unquestionable brand of nationality, religion, gender, and all conceivable categories of how we recognize each other.

I have come to respect the curator far more now that Venice is far away—having seen, and felt, the need for such a show to have been organized on the international stage. Beyond the criticism levied against Pedrosa for his organizational miscalculations, we are at a unique moment in history when the ideals he was advocating require desperate attention: those of acceptance, openness, and the understanding of alienation through a realization of the alien within each of us, no matter where we are, where we are from, who we are with, or who we believe ourselves to be.

Ahmed Umar, Talitin (The Third) (2023-34), still from video and performance. Image courtesy Venice Biennale.

There were definitely major successes, such as Sudan-born Norway-based Ahmed Umar’s powerful performance/video installation, Talitin (The Third) (2023-24). New York has seen artists from the Biennale’s contemporary section emerge and shine within the last few months with Salman Toor’s two-part painting, drawing, and etching solo shows at Luhring Augustine, and the installation of Karimah Ashadu’s short film, Machine Boys (2024), at Canal Projects. History may remember Pedrosa’s Venice Biennale differently when the physicality of the exhibition is forgotten and all that remains are photographs, catalogs, memories, and the dozens of previously unknown artists he introduced to the Western canon. If his actions last year truly end up breaking whatever chains we are still bound by, no one will be happier than I.

NOTES

1. Adriano Pedrosa, “Biennale Arte 2024 | Introduction by Adriano Pedrosa,” La Biennale di Venezia, June 22, 2023, https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2024/introduction-adriano-pedrosa; Gabriella Angeleti, “Curator Adriano Pedrosa Responds to Criticisms of His Venice Biennale Exhibition,” The Art Newspaper - International art news and events, June 10, 2024, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2024/06/10/adriano-pedrosa-responds-criticisms-venice-biennale-exhibition.

2. Zachary Small, “Can Adriano Pedrosa Save the Venice Biennale? No Pressure,” New York Times, April 10, 2024, Arts section, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/10/arts/design/adriano-pedrosa-venice-biennale.html.

3. Kate Brown, “Adriano Pedrosa on His Vision for the Venice Biennale,” Artnet News, April 15, 2024, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/adriano-pedrosa-venice-biennale-2466728.

4. Pedrosa, “Biennale Arte 2024,” https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2024/introduction-adriano-pedrosa.

5. Sean Burns, “Central Pavilion Review: A Celebration of ‘Outsiders’ That Lacks a Punch,” Frieze.com, January 3, 2025, https://www.frieze.com/article/venice-biennale-2024-review-giardini-central-pavilion.

7. Jackson Arn, “The Dead Rise at the Venice Biennale,” The New Yorker, May 2, 2024, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/05/13/venice-biennale-art-review.

8. Alex Greenberger and Maximilíano Durón, “The 2024 Venice Biennale: Our Critics Discuss Their First Impressions of a Show Unlike Any Other,” ARTnews.com, April 19, 2024, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/reviews/the-2024-venice-biennale-our-critics-discuss-their-first-impressions-1234703858/.

9. Jean Fisher, “‘Magiciens de La Terre’ in Paris,” Artforum, September 8, 1989, https://www.artforum.com/events/magiciens-de-la-terre-in-paris-194191/.

10. Davis, “'Foreigners Everywhere,” https://news.artnet.com/art-world/foreigners-everywhere-unpacked-venice-biennale-review-part-3-2485132.

-

Abbas A Malakar is an independent curator from Kolkata, India. He is a graduate of the MA Curatorial Practice program at the School of Visual Arts. His practice spans public media, social practices, and storytelling. From cooking to collective zine-making, Malakar’s focus is deeply rooted in the everyday need for communal gatherings and public programming. Along with independent curatorial projects, he contributes writing to IMPULSE Magazine and to his Substack, Not This Curator.

Of Snakes and Mirrors

What if nature, transfigured by a mirror, redirected its gaze at us, human beasts?

By Bernardo José de Souza

What if nature, transfigured by a mirror, redirected its gaze at us, human beasts?

Bernardo José de Souza • 7/1/25

Adriana Varejão: Don’t Forget, We Come from the Tropics, The Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York, March–June 2025

-

On Site is The Curatorial’s section in which writers review exhibitions from a curatorial perspective—not an art review, a curatorial review. This is also a showcase for master’s degree students in the MA Curatorial Practice program at the School of Visual Arts (the home of the journal) to publish as part of the program—though others are welcome to write for On Site as well.

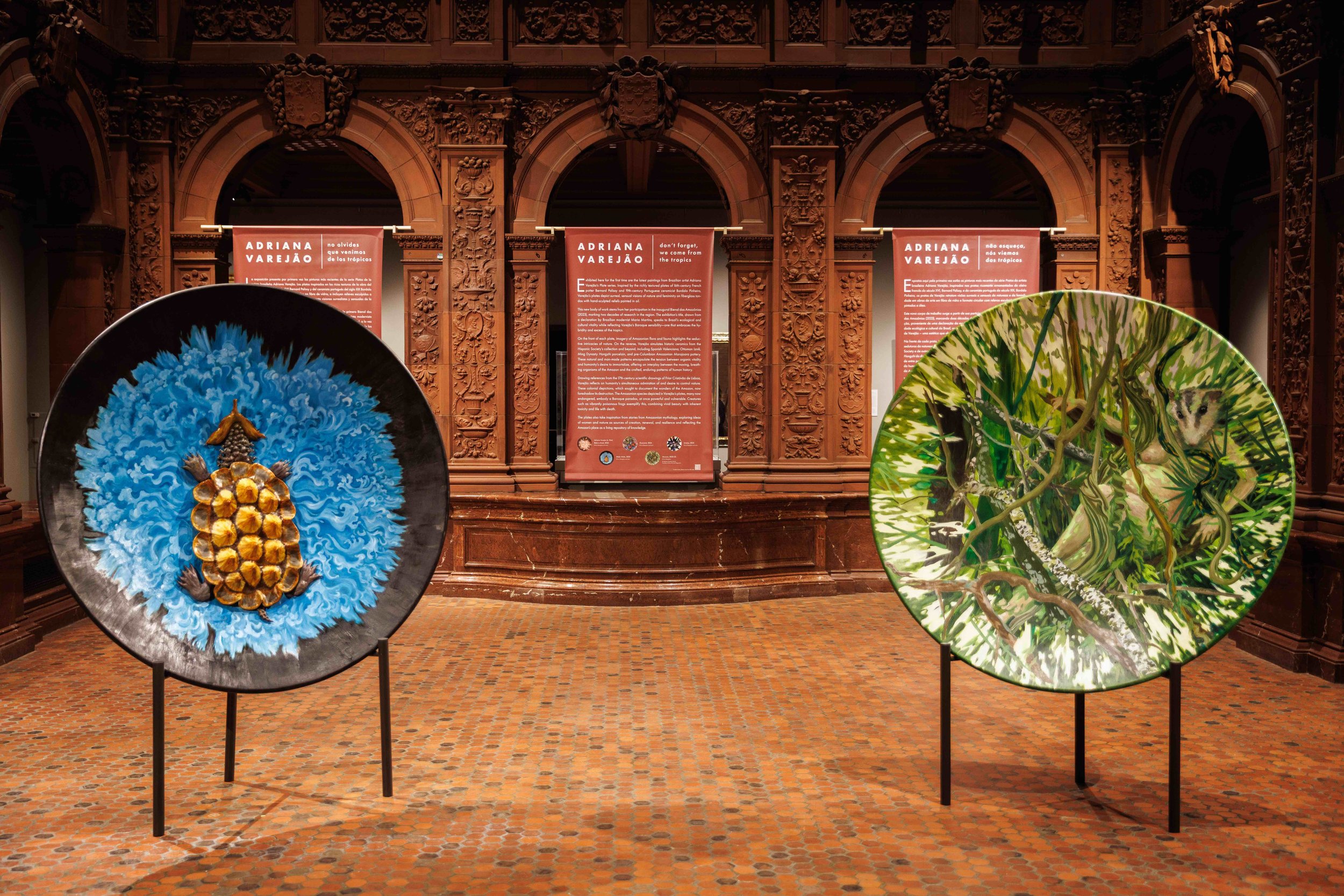

In this review, Bernardo José de Souza examines Don’t Forget, We Come from the Tropics, Adriana Varejão’s exhibition at the Hispanic Society Museum & Library. Engaging with colonial histories, Indigenous cosmologies, and the material language of ceramics, the show challenges Western perceptions of nature and subjectivity. Varejão’s large sculptural plates operate as both mirrors and speculative worlds, prompting a reversal of the gaze. The exhibition is conceptually layered and visually immersive, offering a critical reflection on power, perception, and the role of the museum.

Adriana Varejão: Don’t Forget, We Come from the Tropics exhibition view at the Hispanic Society of America. Image courtesy Gagosian.

By luring our imagination beyond surfaces, Adriana Varejão opens wounds in the fabric of reality, ushering the viewer into devious metaphysical pathways that do not abide by easy dichotomies between animate and inanimate entities. As we look at the bursting flesh emerging from within her signature tiles, what we see are the wondrous renderings of the “natural” world seeping through symbolic and material cultures. Attuned to the interactions between various forms of existence, the Brazilian artist has been producing speculative theory throughout her body of work since the 1980s—and the word “speculate,” of course, has the same etymological root as “specular,” which means to reflect, as a mirror does. The reflections prompted by her artworks transcend her canvases, totems, or plates, as the artist articulates fathoms of performative relations between living matter, material culture, and colonial history. She instills a suprasensory perception of the work, one that entices reasoning and seeing as much as feeling. By arousing a sense of alterity and delving into unacknowledged realms of life beneath the grounds of so-called reality, she awakens the stranger within us.

Adriana Varejão: Don’t Forget, We Come from the Tropics exhibition view at the Hispanic Society of America. Image courtesy Gagosian.

As for her recent exhibition at the Hispanic Society Museum & Library in New York, Don’t Forget, We Come from the Tropics, Varejão enlarges decorative concave plates to the extent that they engulf the body and mind, absorbing us into another dimension—as if we had passed beyond the mirror bound to another world, traversing unknown planes of existence in the manner of Orpheus in Jean Cocteau’s eponymous film. Paraphrasing Brazilian artist Maria Martins’ remark “Don’t forget, I come from the tropics,” the title of the exhibition alludes to an ecology of entities and mythologies that derive as much from the Amazonian rainforest and its Amerindian cosmologies as from scientific views of what the natural realm appears to be or stands for in the West. This alternate reality painted and sculpted by Varejão depicts an overwhelming mélange of living creatures, intertwined, inextricable, indomitable—a wild nature, if you will. The concept of wilderness, however, doesn’t exist in most Amerindian cultures, while what the Occident deems to be nature is only a construct: the Romantic projection of a landscape devised according to an anthropocentric understanding of the universe, in which humankind evades the sovereignty of “natural world,” depicting it in order to forcibly control it.

In this sense, Varejão’s new series of painted and sculpted concave plates places the viewer vis-à-vis other lifeforms, while deconstructing the tradition of two-dimensional landscape paintings. These works led me to think about convex mirrors as seminal, emblematic indexes of Eurocentric civilizations: self-obsessed, self-referential, and largely informed by epistemologies that not only oppose the idea of nature to that of culture but also objectify nature under the unidimensional perspective of humankind, apart from all other living creatures. And here, it’s worth noting that mirrors were among the insidious objects given by Portuguese colonizers to Indigenous peoples, no doubt aiming to instill a corrupting sense of individuality in otherwise holistic cultures.1

*

Circa the fifteenth century, or by the time of the first colonial enterprises across the Atlantic, convex mirrors came into fashion around European aristocratic milieus, offering a pristine reflection of one’s own image—a round surface that diffracted far more light than previous rudimentary brass or silver plates. So much so that painter Jan Van Eyck would use one of these devices in his highly elaborated masterpiece, The Arnolfini Portrait (1434): the artist placed it behind the wedded couple, enabling viewers to scrutinize what they would otherwise have been unable to see—and not merely an external view. As an artistic device, mirrors allow their subjects (at least, in the imagination) to be in intimate contact with their inner natures, which was and is, of course, true for artists who render self-portraits as a way to peer into themselves. According to Ian Mortimer, previously to their existence, “individuality as we understand it today did not exist: People only understood their identity in relation to groups—their household, their manor, their town or parish—and in relation to God.”2 Therefore, one could argue that mirrors ended up sealing the anthropocentric perspective of the human being as both the subject and the object of their own unidimensional view of the world, detached from a communal interaction with the surrounding environment.

Westerners tend to see the natural realm as the double-image of their inner fabrications, informed by an ontological detachment that precedes their sought-after “civilized” world. For the West, humans understand themselves as elevated entities capable of imposing order on the “state of nature” (or absence of order), as postulated by Hobbes, Rousseau, and other Enlightenment thinkers. Notwithstanding, what Varejão appears to achieve with her new series of plates is an excavation of our mirrored inner image of nature—largely inspired by the sixteenth-century ceramics of the French Huguenot potter and engineer Bernard Palissy, as well as the Portuguese artist Bordalo Pinheiro’s nineteenth-century tableware adorned with high-relief animals. So, what if “nature” could look back at us? What would it see?

According to anthropological interpretations of Amerindian animistic cosmologies3 —which favor mobile perspectives and relational configurations between “nature” and “culture”— humans see themselves as humans, and animals as animals, while animals see humans as just another animal: “Predator animals and spirits, however, see humans as prey animals, while prey animals see humans as spirits or as predator animals: ‘The human being sees itself as such. Nonetheless, the moon, the serpent, the tapir and the mother of smallpox see them as a tapir or a peccari, which they kill’, notes Baer about the Machiguenga.”4 Still, according to Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “by seeing us as non-human, they see themselves as humans.”5 In short, “animals are people, or see themselves as such. This conception is almost always associated with the idea that the manifested shape of each species is a wrap (a piece of ‘clothing’) hiding an internal human form, normally only visible to the eyes of its own species.”6

Eschewing the Amerindian perspectivist theories of scholars, though still following their cues, one could entertain the idea that what nature “sees” is a transmogrified version of us. Conversely, the West’s perspective on the natural realm is one that forces a semblance of order by relegating it to sheer randomness, devoid of actual “thinking,” insofar as it denaturalizes the human as a semi-demiurgic being capable of controlling single-handedly the course of life. In this world of human-driven order, nature is deprived of its autonomous agency, its processes, behaviors, and actions.

If Varejão’s plates evoke mirrors, they can also be thought of as magnifying glasses of sorts, offering detailed depictions of universes abundant with mystifying species. Rather than being flattened on the surface, some of these creatures emerge as actual embodiments—three-dimensional beings projecting their existence into the viewer’s space-time dimension. Here, painting and sculpture operate as a kind of reverse trompe l’oeil, in which subject and background are enmeshed. Or, alternatively, where representation, virtuality, and reality all collide. Much in the same fashion of the convex or concave mirrors of the past, her plates appear to distort the image. It seems that what the artist’s magic operates is a reversal of the gaze. In these new works, we no longer see the objectified image of nature, as devised by the Cartesian mindset—instead, nature looks back at us, inverting the subject/object perspective forged by modernity, in which humans scientifically scrutinizes all other lifeforms.

Often deriving from mythologies that originated in the lands known today as Brazil, these painted plates are not meant to be thorough and accurate versions of oral histories found in the Amazon; they depict untimely encounters between species invested with their very own perceptual prowess, some even transcending the empire of vision, which by and large imposes itself above the other senses. In the most convoluted of them all, Guaraná (2024), Varejão creates a virtual nest for rare poisonous reptile and amphibian animals, their mesmerizing colors signaling a pattern of visual communication. Detached from the painted surface, where a profusion of carnivore creatures gets entangled, red seeds of guarana spring open three-dimensionally as if they looked at us from the interior of their black-and-white, eyeball-shaped flesh. And as it follows, akin to this most intricate piece, all her plates will, somehow, explore the gaze of nature upon us humans.

Adriana Varejão: Don’t Forget, We Come from the Tropics exhibition view at the Hispanic Society of America. Image courtesy Gagosian.

In a different work, Urutau (2025), the artist portrays a macabre owl of sorts glaring at us with its fired eyes, surrounded by Amazonian butterflies—this rare insect’s wings flashing out exquisite patterns, as if to deceive the viewer (or the predator?) with its bewildering camouflage colors. Another plate, Mucura (2023-25), will confront us with a mythical figure of the the same name, which translates as Opossum, a marsupial of nocturnal habits, here portrayed as a pregnant animal of semi-human features lying among lianas and trees—this time round, the anthropomorphic figure stares at we humans, standing outside the mirror-plate, as if asking: Who has given birth to whom?

Adriana Varejão: Don’t Forget, We Come from the Tropics exhibition view at the Hispanic Society of America. Image courtesy Gagosian.

On a rather different note, with Boto e Aruá (2025), the artist challenges the primacy of vision as a given in the process of acknowledging the phenomenological world. She devises a plate in which several Boto Cor de Rosa (a folkloric pink dolphin in Amazonia that transforms into a seductive young man) are surrounded by sculpted Aruás do Mato (snails), animals gifted with exploratory antennae that help them smell, taste, touch, and see, reaching for the outer world, rendering the whole of the work an allegory for the entanglement of visible and invisible forces, both tangible and intangible, supposedly real, though just as likely fictitious or mythological. Finally, with Mata Mata (2025), Varejão continues to investigate sensorial aspects of living beings by portraying an Amazonian turtle, its carapace as a shield—disappearance as a strategy for survival: the senses enfolded, allowing for it to disengage with the visible world. The sculpted vessel as enigmatic as the rare species itself, here reproduced by the artist after a drawing made by Frei Cristóvão de Lisboa, a Portuguese priest devoted to zoology.

Adriana Varejão, Boto e Aruá, 2025. Oil on fiberglass and resin. On view at the Hispanic Society of America. Image courtesy Gagosian.

As much as religion and mythology are an attempt to create a rationale for the unfathomable, so is science. What remains to be equated, though, is humankind’s capacity to grasp the social, biological, and cultural realms through its intra-actions with an ecology of other beings, both living and nonliving entities.7

*

Theorizing, a form of experimenting, is about being in touch. What keeps theories alive and lively is being responsible and responsive to the world’s patternings and murmurings.—Karen Barad8

In their 2017 book Are We Human? Notes on an Archeology of Design, Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley inquire into the domain of technology, within which all living entities are captured by the gravitational pull of design. They write: “We live in a time when everything is designed, from our carefully crafted individual looks and online identities to the surrounding galaxies of personal devices, new materials, interfaces, networks, systems, infrastructures, data, chemicals, organisms, and genetic codes.”9 One could argue that from the Amazon rainforest (we now know that it is the product of soil management engineered by its Indigenous population in the distant past) to mythological creatures, myriad constellations drawn on the skies, and even tableware, most of what surrounds us is the product of human ingenuity—technologies (even imagined ones) giving shape to a world devised as an ever-shifting scenario. So, Colomina and Wigley state, “It is precisely the lack of a clear line between human and world that provokes or energizes design as the attempt to fashion a self-image and the forever unsatisfying attempt to come to terms with what we see in this continually reconstructed mirror.”10

In this sense, when looking at the back of Varejão’s free-standing mirror-plates, we are faced with the reproduction of designs of historic ceramics from the Hispanic Museum’s collection and beyond, including Spanish Valenciana, Ottoman Iznik, Ming Dynasty Hongzhi porcelain, and pre-Columbian Amazonian Marajoara pottery. As Louis Vaccara acutely observes in his writing about the exhibition, “The juxtaposition of the two sides of each plate—between natural and man-made patterns—encapsulates a tension between organic vitality and humanity’s desire to immortalize, offering an interplay between the moving, breathing organisms of the Amazon and the crafted, enduring patterns of human history.”11

But when will we acknowledge the rational agency of all beings, not just humans? We typically claim that “natural” patterns are devoid of intellectual intent, of concerted design in this sense. Yet, it is time to acknowledge the intra-action between worldly, human and nonhuman, living and nonliving entities. Aren’t they a precondition for any sort of discursivity? Karen Barad states as much in writing: “Theories are living and breathing reconfigurings of the world,” insofar as “thinking has never been disembodied or uniquely human activity,” and “all life forms (including inanimate forms of liveliness) do theory.”12

Mutatis mutandis, what Varejão provokes when confronting the public with her mirror-plates is a rare sense of unity by dragging the human viewer into phenomenological entanglements with various entities—that is, she confronts us with the idea of “nature” (formulated by Western epistemologies) as an imaginary order, for a fleeting moment releasing us from the constraints of the supposedly objective reality proffered by science. In this way, her plates allow us to see past the Manichaean lens, beyond the horizon of Western binary narratives, through the chimera of wilderness, as it were.

By finding strangeness in what appears familiar, and familiarity in what appears uncanny, we may eventually grasp the sense of alterity that enables us to care for things that are truly singular. “Troubling oneself, or rather, the ‘self’, is at the root of caring,” as Barad remarks.13 Therefore, touching upon another existence entails deconstructing the idea of “us” as opposed to the unknown Other. Ultimately, Varejão prompts us to reflect on our contemporary common solitudes, driving us to grapple with the mythological creatures that emerge from her painterly order to become part of our own world.

Welcoming visitors at the exterior staircase that leadins into the museum’s gardens, an Amazonian Boiúna (Ananconda) sculpted by the artist strangles the equestrian statue of El Cid Campeador (1927, by Anna Hyatt Huntington), vanquishing the colonizing impetus that insists on subordinating all existing creatures and cultures.

Adriana Varejão, Sucuri, 2025. On view at the Hispanic Society of America. Image courtesy Gagosian.

*

The Hispanic Society Museum & Library, founded in 1904 by US scholar, philanthropist, and collector Archer M. Huntington, hosts thousands of books and manuscripts; a multitude of paintings, drawings, and sculpture; and other cultural belongings that date from the Paleolithic period to the twentieth century. Given Varejão’s relentless obsession with and scrutiny of ceramics production across time, multifariously incorporated into her artmaking, the institution invited her to delve into their collection and building with the purpose of renegotiating the contemporary with the past.

Granted full access to its collections—including plates, bowls, jars, and many other ceramic elements, Varejão devised the installation of her works to challenge and disrupt the Spanish Renaissance-style courtyard, with its ornate architectural terracotta. There, her grand plates, measuring nearly six feet in diameter, enact a rather unsettling choreography of bodies and objects: a jeu de miroirs of sorts, facing different directions, diffracting the attention of viewers, whose eyes travel from the background of the main hall into the abyssal foreground of the action that materializes violently through the entanglement of Amazonian species that exceed the margins of her plates. Operating as curator, the artist orchestrates a dialogical clash between her new works and an array of ceramics from Spain, Mexico, and Portugal (dating as far back as the fifteenth century), between interior and exterior (both physical and psychological), between past and present, and between discursive grip and reverie. She lures the public into the open plane of a decolonial debate that shatters the very grounds of the institution-museum—as well as its forceful grasp on historical narratives.

Varejão’s curatorial approach recalls the vision of artist Fred Wilson in his exhibition Mining the Museum: An Installation Confronting History at the Maryland Historical Society, in Baltimore, in 1992-93. where he brought to the surface long-entrenched racist characteristics of the collection and its display, reproposing the very nature of what could be seen in and of the institution. As art historian Terry Smith points out, “institutions such as historical societies and museums, which are presumed to outline a general narrative and to present their materials in as objective a fashion as possible, consistently fail to do so when it comes to socially contentious matters, such as, in this case [the Maryland Historical Society], the history of slavery in the U.S.”14

While producing an “unequal accumulation of time,” juxtaposing and over-imposing distinct layers of history, epistemologies, and cosmologies, Adriana Varejão renders the grand narratives of modernity as flawed attempts to preserve the integrity of Western history.15 Like a crack in a vase, which can be mended, though never fully repaired, her insidious intrusion into the precincts of the Hispanic Museum confers a surreal atmosphere on an exhibition that, through its works’ extraordinary distortions, depicts an integral picture of a world that exists beyond the confines of institutional knowledge.

Adriana Varejão: Don’t Forget, We Come from the Tropics exhibition view at the Hispanic Society of America. Image courtesy Gagosian.

NOTES

1. Marcos Carneiro de Mendonça, A Amazônia na Era Pombalina—Correspondência do governador e capitão-general do estado do grão-pará e maranhão, Francisco Xavier de Mendonça Furtado, 2 edição, Tomo I (Brasília: Ed. do Senado Federal, 2005), 407.

2. Ian Mortimer, “The Mirror Effect,” Lapham’s Quarterly, https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/ mirror-effect.

3. Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, A Inconstância da Alma Selvagem (São Paulo: Cosac Naif, 2011), 355. “The original condition common to humans and animals is not animality, but humanity. The great mythical divide shows less culture distinguishing itself from nature than nature distancing itself from culture. [...] Humans are those who have remained equal to themselves: animals are ex-humans, and not human ex-animals.” (Translated by the author)

4. de Castro, A Inconstância, 350.

5. Ibid., 350.

6. Ibid., 351.

7. “Intra-action is the term used by Karen Barad to indicate agency not as an inherent property of an individual or human to be exercised, but as a dynamism of forces in which all designated ‘things’ are constantly exchanging and diffracting, influencing and working inseparably. Intra-action also acknowledges the impossibility of an absolute separation or classically understood objectivity, in which an apparatus (a technology or medium used to measure a property) or a person using an apparatus are not considered to be part of the process that allows for specifically located ‘outcomes’ or measurement,” to use the words of Whitney Stark when referencing Barad’s book Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham, NC: Duke University, 2007), 141.

8. Karen Barad, “On Touching—the Inhuman That Therefore I Am,” https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.ucsc.edu/dist/1/400/files/2015/01/barad-on-touching.pdf?bid=400, 1.

9. Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, Are We Human? Notes on an Archeology of Design (Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2017), 9.

10. Ibid., 25.

11. Louis Vaccara, “Adriana Varejão: Don’t Forget, We Come from the Tropics,” Gagosian Quarterly (Summer 2025): 168.

12. Barad, “On Touching,” 2.

13. Barad, “On Touching,” 8.

14. Terry Smith, Thinking Contemporary Curating (New York: Independent Curators International, 2012): 122.

15. According to geographer Milton Santos, space is a result of the unequal accumulation of time: layers of geological, natural, human, and technological agents that, in totality, engender history and its intrinsic relationship with political, social, and economic forces. See Milton Santos, The Nature of Space, trans. Brenda Baletti (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021).

-

Bernardo José de Souza worked as artistic director of Fundação Iberê Camargo, in Porto Alegre, Brazil, from where he departed in early 2019 to work as an independent curator based in Madrid and Rio de Janeiro. He was part of the curatorial team of Videobrasil Biennial, held in São Paulo in 2015, and also a member of Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy's curatorial team in the 9th Mercosul Biennial | Porto Alegre Brazil in 2013. From 2005 to 2013, he worked as the Director of the Department of Cinema, Video, and Photography at the Secretary of Culture of Porto Alegre, Brazil. For the past decade, he has been developing several projects in the visual arts field, including exhibitions, film programs, seminars, and publications, as well as educational programs, many of which developed in collaboration with institutions in Brazil and abroad, such as the Goethe Institute, Instituto Inhotin, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Prince Claus Fund, Mondriaan Fund, Institut Français, among others.

At the Edge of Ailey

While the exhibition offers a dizzying spectacle and aims to transcend disciplinary borders, it remains rooted in largely static visual art forms—ironic for a show dedicated to a master of movement.

By Tom Koren

Tom Koren • 2/1/25

Edges of Ailey, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 2024–February 2025

-

On Site is The Curatorial’s section in which writers review exhibitions from a curatorial perspective—not an art review, a curatorial review. This is also a showcase for master’s degree students in the MA Curatorial Practice program at the School of Visual Arts (the home of the journal) to publish as part of the program—though others are welcome to write for On Site as well.

In this review, Adrienne Edwards’s groundbreaking exhibition, concerned with the choreographer Alvin Ailey, is critiqued. The exhibition offers a variety of approaches to delve into Ailey’s work and cultural context. It is spectacular and challenging in ways that are both informative and problematic for our reviewer.

As the Whitney Museum elevator doors open onto the fifth-floor galleries, the Edges of Ailey audience is met with a dizzying spectacle. The vastness of the open space, the dramatically dimmed spotlights, the luscious burgundy walls, the abundance of artworks, and the multi-channel video panorama that envelops the gallery—its soulful and propulsive soundtrack reverberating throughout—combine into a glamorous theatricality, making it feel as though one has emerged directly onto an active stage.

Installation view of Edges of Ailey (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 25, 2024-February 9, 2025). From left to right: Romare Bearden, “The Father Comes Home” from the Bayou Fever series, 1979; Romare Bearden, “Wife and Child in Cabin” from the Bayou Fever series, 1979; Romare Bearden, “The Herb Woman” from the Bayou Fever series, 1979; Romare Bearden, “The Mother Hears the Train” from the Bayou Fever series, 1979; Robert Duncanson, View of Cincinnati, Ohio from Covington, Kentucky, c. 1851; Mary Lovelace O’Neal, Race Woman Series #7, c. 1990s; Jean-Michel Basquiat, Hollywood Africans, 1983; Emma Amos, Judith Jamison as Josephine Baker, 1985; Kerry James Marshall, Souvenir IV, 1998; Ellsworth Ausby, Untitled, 1970; Lorna Simpson, Momentum, 2011; Kandis Williams, Black Box, 4 points: Horton, Ailey, McKayle contractions and expansions of drama from vernacular –– arms outstretched and entangle, 2021; Jacob Lawrence, Figure Study, c. 1970; Terry Adkins, Other Bloods (from The Principalities), 2012; James Little, Stars and Stripes, 2021; Rashid Johnson, Untitled Anxious Men, 2016; Glenn Ligon, Stranger in the Village #12, 1998. Photograph by Ron Amstutz. All images courtesy the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Edges of Ailey, curated by Adrienne Edwards, the Engell Speyer Family Curator and Curator of Performance at the Whitney, honors the trailblazing choreographer Alvin Ailey (1931–1989) and the legacy of his eponymous dance company, founded in 1958 and active to this day. Drawing on Ailey’s innovative, cross-disciplinary, and tentacular approach to modern dance—with inspirations ranging from literature and poetry, music and art, theater and cinema, to history, politics, community, and spirituality—the exhibition seeks to explore and pay homage to the roots and impact of his practice through a unique presentation of visual art complemented by a live dance program in the museum’s theater.

From left to right: Ellsworth Ausby, Untitled, 1970; Kerry James Marshall, Souvenir IV, 1998; Beauford Delaney, Charlie Parker Yardbird, 1958; Norman Lewis, Phantasy II, 1946; Sam Gilliam, Swing 64, 1964; Loïs Mailou Jones, Jennie, 1943; Betye Saar, I’ve Got Rhythm, 1972; Charles Gaines, Sound Box: Nina Simone and Billie Holiday, 2021; Jean-Michel Basquiat, Hollywood Africans, 1983; Romare Bearden, “The Father Comes Home” from the Bayou Fever series, 1979; Romare Bearden, “Wife and Child in Cabin” from the Bayou Fever series, 1979; Romare Bearden, ”The Swamp Witch” from the Bayou Fever series, 1979; Romare Bearden, “The Blue Demons” from the Bayou Fever series, 1979; Romare Bearden, “The Wart Hog” from the Bayou Fever series, 1979; Romare Bearden, “The Lizard” from the Bayou Fever series, 1979; Romare Bearden, “The Hatchet Man” from the Bayou Fever series, 1979. Photograph by Ron Amstutz.

Ailey’s visionary spirit is reflected mainly in the exhibition design. The decision to open up the entire gallery space is daring; there are hardly any separations, and the entirety of the show becomes visible at a glance. Paintings and sculptures are grouped in archipelagos in the center of the space, propped against dark red backings or suspended from the ceiling in a free-standing, Lina Bo Bardi fashion, while other sections of artworks hang on the surrounding walls beneath the video installation. The exhibition includes works from the Whitney’s collection alongside some loans and commissions, all intended to represent or respond to the elements that made up Ailey’s life and artistic persona, together forming one multilayered portrait of the choreographer and an encompassing visualization of Black dance. Interwoven throughout the artworks are personal notebooks, postcards, books, photographs, posters, and other Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT) ephemera, densely aggregated inside vitrines. The curatorial strategy aims to form “constellations” that resist a linear or hierarchical narrative, blurring the boundaries between the disciplines and themes that shaped Ailey’s choreography. While this curatorial approach works well conceptually—successfully restaging the multidimensionality, richness, and breadth of Ailey’s influences and accurately capturing the spirit of the time inherent to his practice—there is a sense that the concept comes at the expense of the artworks. The floating islands and dense hanging of works create a slightly disorienting dramaturgy for the audience, resulting in a sight that is as aesthetically dazzling as it is overwhelming, leading to a somewhat superficial encounter with the art on display.

From left to right: Romare Bearden, “Star (Star from the Heavens)” from the Bayou Fever series, 1979; Archibald John Motley Jr., Gettin’ Religion, 1948; Roy DeCarava, Coltrane and Elvin, 1960; Roy DeCarava, Elvin Jones, 1961; Lyle Ashton Harris, Billie #21, 2002; Hale Aspacio Woodruff, Blind Musician, 1935/1998; Norman Lewis, Jazz, 1943–44; Gordon Parks, Music–That Lordly Power, 1993; Mary Lovelace O’Neal, Race Woman Series #7, c. 1990s; Terry Adkins, Other Bloods (from The Principalities), 2012; Bill Traylor, Untitled (Man in a Blue House), date unknown; Ralph Lemon, Bongos and Djembe, 1999; Ralph Lemon, Untitled (On Black music), 2001-07; Ralph Lemon, Untitled (Miles Davis), 2006; Mickalene Thomas, Katherine Dunham: Revelation, 2024. Photograph by Ron Amstutz.

The selection of artworks elegantly unpacks the era and situates Ailey’s oeuvre within a larger sociopolitical context, tying an important interdisciplinary link between his many realms of influence and the figures he was in dialogue with. The focus on his upbringing in the American South and the historical emphasis on Black migration and liberation work to elucidate just how groundbreaking and unprecedented his worldwide success was at the time. That being said, the sensory overload resulting from the large amount of works, their clustered, salon-style hanging, and the all-encompassing presence of the video installation limits a deeper engagement with each thematic section and with the individual pieces within it. The thematic groupings often feel loose or associative, with artworks serving as explicit visualizations of broad and abstract topics. For instance, the section dedicated to the influence of Black women on Ailey’s life includes paintings of Black women or mothers, while his struggle with mental health is illustrated by Rashid Johnson’s Untitled Anxious Men (2016), which depicts an abstracted and distraught figure, its features frenetically etched into thick black wax. While the porousness of the different sections is intended as part of the constellational curatorial vision, they are at times confusing to navigate through. This isn’t always made easier by the didactics, which are often too small or placed in strange, inconvenient locations such as the floor or in the middle of a section, surfacing only after you’ve spent a moment wondering what you are looking at and how it ties into the exhibition. To a viewer who isn’t well versed in Ailey’s world, this makes it difficult to distinguish which of the artworks have a direct connection to his life or practice, and which are included to illustrate abstract elements of his biography. The juxtapositions of the works rarely form illuminating conceptual connections that enhance their individual presence or enrich the internal logic of each section, resulting in a whole that may be greater than the sum of its parts, yet, on balance, offers a spectacle that is somewhat flattening.

From left to right: Sam Doyle, Frank Capers, 2023; Sam Doyle, LeBe, 1970s; Wadsworth Jarrell, Together We Will Win, 1973; Faith Ringgold, United States of Attica, 1971; Wadsworth Jarrell, Revolutionary (Angela Davis), 1972; James Van Der Zee, Marcus Garvey Rally, 1924; Jeff Donaldson, Soweto/So We Too, 1979. Photograph by Ron Amstutz.

To the left of the exhibition space is a section of archival ephemera, dominated by a double-sided row of old TV monitors that plays black-and-white videos. The source materials are dedicated to Ailey’s influences and collaborators, ranging from specific choreographers, artists, and musicians to broader themes like Hollywood or Broadway. These are also inadequately contextualized in the didactics. Their connection to his practice is often too unclear or too loose, and the lack of seating doesn’t aid viewers in the extended type of engagement that can illuminate the works or inspire the audience. In the absence of time-based media that actually depicts Ailey’s practice itself, the amount of videos dedicated to his influences is disproportionate, lacking anything substantial for viewers to tie it back to. This also applies to the archival documents presented in vitrines throughout the space, where Ailey’s personal notebooks and correspondences mainly function as material relics since they are usually too illegible to consume as content.

From left to right: Alma Thomas, Mars Dust, 1972; Charles White, Preacher, 1952; Lonnie Holley, Sharing the Struggle, 2018; Benny Andrews, The Way to the Promised Land, 1994; Sam Doyle, Frank Capers, 2023; Sam Doyle, LeBe, 1970s; Wadsworth Jarrell, Together We Will Win, 1973; Faith Ringgold, United States of Attica, 1971; Wadsworth Jarrell, Revolutionary (Angela Davis), 1972; James Van Der Zee, Marcus Garvey Rally, 1924; Jeff Donaldson, Soweto/So We Too, 1979; Horace Pippin, School Studies, 1944; Horace Pippin, Cabin in the Cotton, c. 1931–37; Horace Pippin, Knowledge of God, 1944; William H. Johnson, At Home in the Evening, c. 1940; John Biggers, Sharecropper, 1945; Robert Duncanson, View of Cincinnati, Ohio from Covington, Kentucky, c. 1851; Joe Overstreet, Purple Flight, 1971; Emma Amos, Judith Jamison as Josephine Baker, 1985; Kerry James Marshall, Souvenir IV, 1998; Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, A Knave Made Manifest, 2024; Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Fly Trap, 2024; Missa Marmalstein and other makers unknown, Block 1871 of the AIDS Memorial Quilt, 1987. Photograph by Ron Amstutz.

It is important to note that the decision to represent dance through various mediums—showcasing not only Ailey's choreography but also his concerns, the art that interested him, and the art that bounds the experience of Blackness—is, of course, an important endeavor—and one that continues the correction of the historical imbalance of the representation of Black artists in American institutions, both in collections and exhibitions. But are paintings and objects really the best way to convey the history and legacy of dance? One thing that starkly stands out about the exhibition is that, despite its insertion of dance into the museum, Edges of Ailey upholds the traditional division of visual art and live performance. While the exhibition design and content do transcend disciplinary borders in various ways, the show is largely made up of conventional, two-dimensional, static visual art forms. Described as a “dynamic showcase” by the Whitney website, the exhibition is surprisingly dominated by a stillness of objects, despite the presence of scattered videos, as well as the video frieze atop one long wall of the space. The artworks remain divided from live performance, which is relegated to a separate black-box theater’s ticketed performances in allocated time slots. Considering that the show was initiated by a renowned curator of performance art, it would have been interesting to include a durational, unpredictable, or experimental live element within the gallery space.

From left to right: Maren Hassinger, River, 1972/2012; Melvin Edwards, Utonga (Lynch Fragment), 1988; Aaron Douglas, Bravado, 1926; Melvin Edwards, Chitungwiza from the Lynch Fragment series, 1989; Aaron Douglas, Flight, 1926; Melvin Edwards, Katura from the Lynch Fragment series, 1986; Aaron Douglas, Surrender, 1970; Melvin Edwards, Cup of? From the Lynch Fragment series, 1988. Photograph by Ron Amstutz

Even the musical aspects of Ailey’s practice are referenced illustratively and two-dimensionally, with paintings of instruments and a Billie Holiday photograph standing in for more creative auditory forms. The only music that is vibrantly present comes from that sprawling 18-channel video frieze, which is the one truly dynamic and innovative element in the show. The hour-long, looping montage features footage from the AAADT archive paired with a soundtrack of both timeless and contemporary music—ranging from Pharoah Sanders to Donny Hathaway to House music cuts—that is overlaid with interview clips. However, the video’s elevated placement causes it to function more decoratively as a backdrop to the still works, rather than as an artwork in its own right. This feeling is amplified by the fact that the video is uncredited and unexplained within the gallery space, with details about its creators—filmmakers Josh Begley, Kya Lou, and the curator—available only on the website. Were there additional time-based or performative media within the exhibition that referenced Ailey’s practice, this panoramic strip would have sufficed as a curatorial element alone.

From left to right: Purvis Young, Ocean, 1975; Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Mold for Crusaders for Freedom, 1962; Sam Gilliam, Untitled (Black), 1978; David Hammons, Untitled, 1992; Al Loving, Untitled, c. 1975; Hale Aspacio Woodruff, By Parties Unknown, 1935, printed 1996; Hale Aspacio Woodruff, Giddap, 1935, printed 1996; Purvis Young, I Love Your America, late 1970s; Martin Puryear, The Rest, 2009-10; Samella Lewis, Migrants, 1968; Purvis Young, Black People Migrating West, late 1970s; William H. Johnson, Moon Over Harlem, 1943-44; Lonnie Holley, Sharing the Struggle, 2018; Theaster Gates, Minority Majority, 2012; Sam Doyle, Frank Capers, 2023; Sam Doyle, LeBe, 1970s; Wadsworth Jarrell, Together We Will Win, 1973; Faith Ringgold, United States of Attica, 1971; Wadsworth Jarrell, Revolutionary (Angela Davis), 1972; James Van Der Zee, Marcus Garvey Rally, 1924; Jeff Donaldson, Soweto/So We Too, 1979; Maren Hassinger, River, 1972/2012; Melvin Edwards, Utonga (Lynch Fragment), 1988; Aaron Douglas, Bravado, 1926; Melvin Edwards, Chitungwiza from the Lynch Fragment series, 1989; Aaron Douglas, Flight, 1926; Melvin Edwards, Katura from the Lynch Fragment series, 1986; Aaron Douglas, Surrender, 1970; Melvin Edwards, Cup of? From the Lynch Fragment series, 1988. Photograph by Ron Amstutz.

While this immersive video installation is mesmerizing and atmospheric, its fast-paced edits offer limited insight into the essence of Ailey’s choreography. Without prior familiarity with his work or access to the museum’s sold-out performances, I left the show without any clear sense of what Ailey’s choreography is actually like. Ultimately, while the exhibition aims to celebrate Ailey’s groundbreaking legacy and cross-disciplinary influence, it fails to foundationally destabilize disciplinary boundaries in practice, or to reimagine new ways of presenting an archive through performance. By relying on representations instead of recreations and pointing at ideas instead of performing them, Edges of Ailey looks backward, surveying the past more than it experiments with possibilities for the future.

In vitrine, from left to right: Elizabeth Catlett, I am the Negro Woman, 1947, printed 1989; Elizabeth Catlett, In Harriet Tubman I helped hundreds to freedom, 1946, printed 1989; Elizabeth Catlett, In Sojourner Truth I fought for the rights of women as well as Negroes, 1947, printed 1989; Elizabeth Catlett, In Phillis Wheatley I proved intellectual equality in the midst of slavery, 1946, printed 1989; From left to right: Kara Walker, African/American, 1998; Karon Davis, Dear Mama, 2024; Geoffrey Holder, Portrait of Carmen de Lavallade, 1976; Beauford Delaney, Marian Anderson, 1965; Loïs Mailou Jones, Jennie, 1943; Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Mother and Child (Secret Sorrow), c. 1914. Photograph by Ron Amstutz.

-

Tom Koren is currently a student in the MA Curatorial Practice program at the School of Visual Arts, New York. She received her B.A in Art History and English Literature at the Tel Aviv University. Her professional experience is rooted in the music field, working as a curator, DJ, marketing manager and creative director for leading alternative cultural institutions and events in Tel Aviv. She has recently been awarded a Fulbright fellowship in the Public Humanities program, with which she aims to merge her academic and professional backgrounds by crossing over to the visual art field, experimenting with the curation of interdisciplinary events and further exploring her interest in participatory and live art practices.