The Sovereign Fox Persuades Law to Dissolve into Politics

The juridical ambitions of Zasha Colah for her edition of the biennale were laudable, but elusive as her symbolic fox.

By Sophie Barfod

The juridical ambitions of Zasha Colah for her edition of the Biennale were laudable, but as elusive as her symbolic fox.

Sophie Barfod • 1/23/25

passing the fugitive on, 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, Berlin, June 14 – September 14, 2025

-

On Site is The Curatorial’s section in which writers review exhibitions from a curatorial perspective—not an art review, a curatorial review. This is also a showcase for master’s degree students in the MA Curatorial Practice program at the School of Visual Arts (the home of the journal) to publish as part of the program—though others are welcome to write for On Site as well.

In this review, Sophie Barfod examines the 13th Berlin Biennale, passing the fugitive on (2025), curated by Zasha Colah, focusing on its use of dramaturgy to frame law, justice, and activism. Structured as a dispersed performance in which viewers are cast as jurors and artworks function as evidence, the Biennale presents law as mutable and performative, gesturing toward fugitivity as an ethical response to lawful violence. Barfod critically evaluates how this approach engages Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL), historical instances of immoral legality, and contemporary artistic practices that destabilize juridical authority, ultimately arguing that the exhibition’s reliance on ambiguity functions as a protective curatorial condition.

Zasha Colah cast her Berlin Biennale, titled passing the fugitive on (June 14–September 14, 2025), as a kind of performance theater spread among four different locations. The drama inherent in using performance theater as a curatorial approach seems an effective attempt to draw in contemporary (often attentionless) art viewers. To that end, the Biennale presented sixty artists and more than one hundred seventy works of art, intending to stimulate a debate on how to position oneself in relation to repressive contexts. Criticism has arisen about the irony of curating a show that apparently seeks justice, while “the viewer is invited to think about almost everywhere but Gaza.”1 It has been argued that the Biennale gravitated toward safer forms of activism, operating within what critics have described as a frame of complicit silence. The Biennale chose to omit geopolitical contexts where global demands for justice continue to be most pressing, therefore aligning itself with sites of political power that prefer such conflicts to remain unspoken.2 This essay examines how justice is articulated curatorially and asks whether legal questions framed through implicit dramaturgy can sustain an activist claim under conditions of political urgency.

Artcom Platform stages a silent monument commemorating the individuals in Kazakhstan who were killed, detained or tortured in 2022 in the uprising known as “Bloody January.” Image: Elisa Carollo.

Colah’s exhibition as a construct operates within the register of the performative, in which passing the fugitive on employs dramaturgy as the primary curatorial intervention. Dramaturgy is traditionally examined curatorially through the ways in which a theatrical setting opposes the standard white cube as a site for display. Even though the Biennale employed scenographic strategies—such as the black-box theater exhibition room at the Hamburger Bahnhof—its staging more generally functioned as a forum for judgment, in which meaning was produced through assigned roles and procedural relations rather than through the white-cube logic of autonomous aesthetic experience.3 Visitors were cast as a public jury, artworks functioned as evidence, and the curatorial framework assumed the position of a closing argument. Such role assignment exceeds metaphor and enters the logic of juridical theater, where interpretation is inseparable from performance. The exhibition space becomes a stage on which judgment is rehearsed rather than resolved. This reveals the risk embedded in this approach: moral interpretation grants judges—and here, viewers—a wide margin for discretion, opening the door to judicial overreach. By asking the audience to “judge the judge,” Colah foregrounds law as a malleable construct, one that is subject to performance and perception. Authority shifts from the institution to the individual, where the viewer becomes the arbiter of moral principles. Some argue that legal interpretation, whether within legal institutions or artistic contexts, is ultimately dependent on collective belief, meaning it is ideological and subject to biases. In the Biennale, Colah seems to shift legal interpretation from legal institutions to aesthetic and social performances, allowing its audience to reflect on their own biases and beliefs in relation to morality.

The Biennale’s central motif is the fugitive fox, a creature that does not break laws but lives indifferently to them. Hence the title, passing the fugitive on: an instruction to carry evidence in body and memory until the right moment to relay it.4 Colah uses the imagery of the fox to pass the idea of fugitivity on to others as an activist gesture and ambition. In the catalogue, she defines this state as the cultural capacity of art to set its own laws in the face of lawful violence, moving outside the law’s demand to be acknowledged. What Colah presents, then, is not merely the fact that law is interpreted, but the possibility of a different horizon for justice, one in which legality gives way to justified resistance and social struggle. Here she converges with the legal movement called Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL), which reframes justice as an ongoing negotiation that takes into account colonial histories, structural asymmetries, and the voices of the marginalized. Critics of TWAIL argue that framing justice as “struggle” or “resistance” risks being too open-ended. If justice is always contested, what are the concrete standards? How do we know when justice is achieved or when resistance itself becomes oppressive?5

The former courthouse on Lehrter Straße, 2025. Image: Raise Galofre.

Colah aims to answer this question with the Biennale’s exhibition section titled “Legality, Illegality, and the Artist’s Claim,” set in the former courthouse on Lehrter Straße. Colah utilizes the site itself as a curatorial argument by excavating the building’s history, as it was the site of the 1916 trial of the German socialist politician and anti-war revolutionary Karl Liebknecht. Prosecuted under wartime censorship laws for his participation in anti-war demonstrations and his criticism of the German military, Liebknecht was a key figure in debate on immoral legality. As the only member of the German parliament to openly oppose the country’s involvement in the First World War, his stance on anti-militarism marked a significant rupture within the legal order.6 Colah mobilizes this legacy by framing the exhibition vis-à-vis this conflict, which was later widely read as unjust. She treats the building less as a neutral container than as an archive of historical institutional immorality. Yet this curatorial precision risks evaporating at the level of encounter. If the historical hinge is legible only in the catalogue, then the exhibition’s ethics remain essentially invisible. For a project that leans on dramaturgy, that’s a structural inconsistency: the trial’s “whispers” should have been staged as part of the exhibition’s script, materialized through some form of scenography or explicit interpretive cues, so that the viewer meets the curatorial argument in space.

Simon Wachmuth’s work plays into this eerie sense of legal injustice with his video commission From Heaven High (2025). In the first half of the work, a black-and-white performance confronts the viewer with the figure of a marching, literally pig-headed soldier at Tempelhofer Feld, where the stark imagery is juxtaposed with Martin Luther’s sacred hymn, “Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her” (From Heaven High I Come). Once repurposed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to support German imperial ambitions, the hymn’s inclusion highlights how cultural symbols have historically been used to sacralize the state and advance nationalist agendas.

Simon Wachsmuth, From Heaven High, 2025, installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, former courthouse on Lehrter Straße, 2025. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025; Zilberman Berlin/Istanbul. Image: Eberle & Eisfeld.

Wachmuth uses this once-sacred hymn to critique the myth of neutrality in cultural heritage, and instead creates a sinister scene concerned with (in)justice. Marching—once a sign of discipline and unity—now becomes a symbol of militarism as performative theater. Wachmuth extends this theatricality into the courtroom that’s shown in the second half of the video, where the logic of militarism is ridiculed further. He presents the scene of a trial as a dramatically lit space in which the very notion of impartiality is replaced by the theatrics of the judge, who declares: “I’ll decide who’s bad and who gets sentenced.” The sovereign tone projects authoritarian overreach, signaling how personal (im)moral judgment, not law, guides decisions. Wachmuth uses this allegory to critique creeping authoritarianism and the erosion of democratic safeguards, hinting at “rule by man, not the law.”7

From Heaven High illustrates the way unlawful directives can issue from the law, calling the very grounding of the law as “blind justice” into question. The work draws on John Heartfield and Rudolf Schlichter’s 1920 Dada installation, Prussian Archangel, at the International Dada Fair in Berlin. It featured a pig-headed papier-mâché soldier with a wire-mesh body hanging from the ceiling, responding to the dubious moral righteousness of military (Prussian) officers in the wake of the disasters of the First World War.8 The original work included an absurd instruction that mirrored the absurdity of war logic, stating that “to fully comprehend this work of art, one should exercise for twelve hours a day on the Tempelhofer Feld with a fully packed backpack and equipped for a field march.” This satirical directive mimics Dada’s anti-war stance, and Wachmuth takes the absurdity of obedience to nationalism as a crude practice at the hands of pigs (sorry, pigs!) and enacts it in his video.

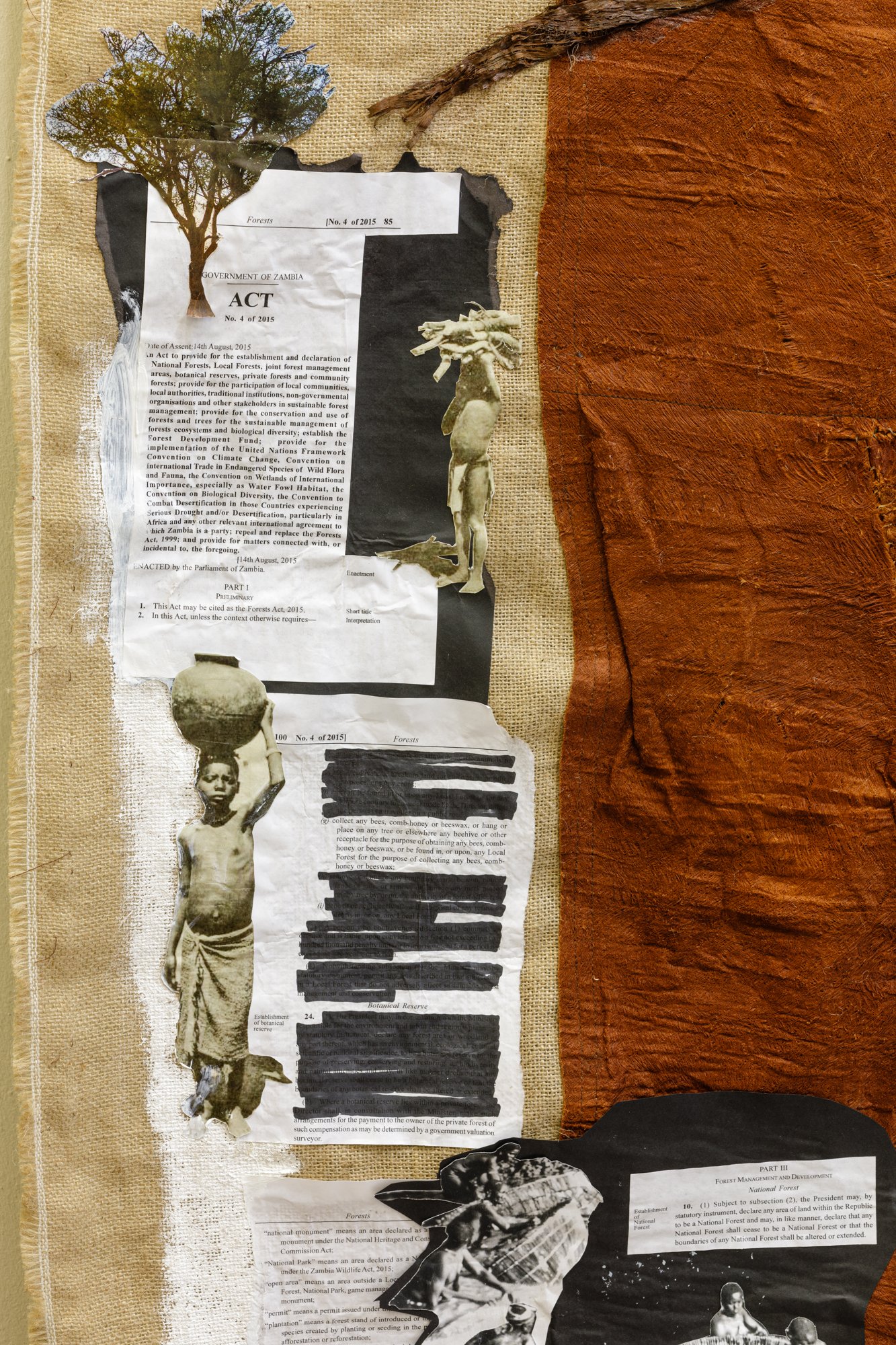

Isaac Kalambata’s collage work Mizyu (2025) seems to be a curatorial illustration of the impact of lawful immorality. Kalambata’s work showcases Zambian legislation on forests and property laws (No. 4 of 2025) with the word “DISPLACED” stamped in red on top of copies of the legislation, illustrating the ways in which the corrupt force of law has brought the displacement of Indigenous populations. The work is accompanied by photographs of what appear to be natives and their belongings. In the center of the piece, we see Mwendanjangula, the “Lord of the Forest,” with his hands tied behind him, eternally attached to a tree. The metaphor touches on the continuous battle between “development” in the eyes of the capitalist beholder and violence in the eyes of the subjugated. Mizyu draws inspiration from the Witchcraft Act of 1914, “a legislation that expressly sought to entrench the colonial Christian church by curtailing alternative spirituality and healing practices within what is now Zambia.” Colah, with the choice of this work, seems to criticize a porous distinction between “this is law” and “this ought to be law.”

Isaac Kalambata, Mizyu, 2025, detail, 13th Berlin Biennale, former courthouse on Lehrter Straße. Courtesy Isaac Kalambata. Image: Eberle & Eisfeld.

One question still lingers after seeing the thirteenth iteration of the Berlin Biennale: if justice is always contested, what are the standards on which it is based and can be counted on in civil societies? Colah’s curatorial approach persuades us to see law as malleable, contingent, and fugitive. TWAIL scholarship affirms this vision, as previously noted, by reframing justice as resistance, as an alternative horizon that refuses colonial hierarchies. In line with the critique that this approach can collapse into ambiguity, the late legal scholar Ronald Dworkin argued that law is always a matter of interpretation, with precedent neither rigid nor random. Yet it must offer integrity and moral validity. In the case of lawful violence, rejecting the law is acting in accordance with a deeper moral logic of the legal system. Essential to this is the discipline of principled interpretation; if everything is up for debate, integrity is lost and law dissolves into politics.9 Between these poles, Colah proposes that the fugitive fox that lives outside of the law, and whose figure suggests that law dissolves into politics, offers neither stability nor certainty. Instead, the fox is a provocation to reimagine the grounds on which justice stands.

Yet the Biennale stops short of articulating what, concretely, should replace that compromised ground. Fugitivity appears as the implied answer—an ethics of refusal, of moving beyond the law’s demand to be acknowledged—but it remains more mood than method. Indeed, the visitor is left with “a sense of a fox with its feet tied.”10 Part of this restraint may be structural rather than accidental: as a publicly funded platform, the Biennale cannot easily stage a critical political position without risking the charge of turning public culture into a partisan mandate.

Colah’s solution is to distribute judgment outward, where the viewers become the jury, and the exhibition provides tools rather than verdicts. But this redistribution produces its own problem. Advocacy requires a legible call and a transmissible ethics—something that can travel beyond the exhibition as more than ambiguity. If fugitivity is meant to be “passed on” as an activist ambition, the dramaturgical conceit promised by the Biennale demanded more than inference; it demands a legible call. Without clearer cues inside the exhibition’s curatorial script, the viewer is left to author the politics alone. In this sense, ambiguity functions as a protective condition. It is even possible that this suspension of principled interpretation was intentional. The Biennale’s reliance on ambiguity seems a wager for the consequences of advocacy to remain hidden, echoing the logic of the fox that survives by remaining elusive, but in doing so cannot be passed on.

Daniel Gustav Cramer, Fox & Coyote, 2024/25. Image: © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2025. Courtesy Sies + Höke, SpazioA, Vera Cortes, Yvon Lambert.

NOTES

1. Martin Herbert, “13th Berlin Biennale Review: What Doesn’t the Fox Say,” ArtReview, September 5, 2025, https://artreview.com/13th-berlin-biennale-for-contemporary-art-various-venues-berlin-review-martin-herbert/.

2. Andrea Scrima, “The Berlin Biennale’s Complicit Silence,” Hyperallergic, July 30, 2025, https://hyperallergic.com/berlin-biennale-complicit-silence/.

3. Colah’s iteration of the Berlin Biennale included four venues. The largest part of the exhibition took place at KW Institute for Contemporary Art. The other venues were the Hamburger Bahnhof–National Gallery for Contemporary Art, Sophiensæle, and the former courthouse on Lehrter Straße.

4. Zasha Colah and Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, eds., 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art: catalogue. (Berlin: Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, 2025).

5. Naz K. Modirzadeh, “‘Let Us All Agree to Die a Little:’ TWAIL’s Unfulfilled Promise,” Harvard International Law Journal 65, no. 1 (Winter 2024): 25–68.

6. John Simkin, “Karl Liebknecht,” Spartacus Educational, updated January 2020, https://spartacus-educational.com/GERliebknecht.htm.

7. Editor’s Note: In this regard, it is worth noting that when The New York Times asked President Donald Trump if there were any limits on his global powers, he replied: “Yeah, there is one thing. My own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me.” https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/08/us/politics/trump-interview-power-morality.html.

8. Simon Wachmuth, From Heaven High (2025). Wall label, 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, former courthouse on Lehrter Straße, Berlin.

9. Ronald Dworkin, Law’s Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986).

10. Herbert, “13th Berlin Biennale Review.”

-

Sophie Barfod is an independent curator from Amsterdam, the Netherlands. She works at the intersection of curating and strategy, currently contributing to W.A.G.E. and SaveArtSpace. Her practice is focused on curating in found spaces, with exhibition concepts often rooted in feminist theory and social practice work. She is currently a student in the MA Curatorial Practice program at the School of Visual Arts, with a Bachelor’s degree (honors) in Politics, Psychology, Law, and Economics from the University of Amsterdam. She has held positions at YAG (McKinsey partner), Heineken, Julietta Alvarez Galeria, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, and is an ex-founder of an experimental arts and technology startup in Amsterdam.

Outsideness, and Other Words of Advice for Young Curators

The problem, especially for emerging curators, should not be how to get inside the sphere and sensibility of rote privilege and power in the art world and exhibition-making, but how to stay out of them.

By Niels Van Tomme

The problem, especially for emerging curators, should not be how to get inside the sphere and sensibility of rote privilege and power in the art world and exhibition-making, but how to stay out of them.

Niels Van Tomme • 12/9/25

-

Critical Curating is The Curatorial’s section devoted to more theoretically oriented considerations of curatorial research and practice. While of a specialized nature, we seek essays for this section that are written for a broadly engaged intellectual audience interested in curating’s philosophical, historical, aesthetic, political, and social tenets, as well as a labor-based activity and its ramifications.

In “Outsideness, and Other Words of Advice for Young Curators,” Niels Van Tomme reframes the desire to “enter the art world” by proposing outsideness—adapted from Mikhail Bakhtin’s phrase, “excess of seeing”—as a productive curatorial orientation. Reflecting on his directorship of De Appel’s Curatorial Programme, Van Tomme contrasts the institution’s early experimental ethos with the professionalized expectations that later narrowed its scope. He argues for curatorial practices that resist standardized exhibition formats, privilege deep collaboration with artists, and cultivate forms of publicness not bound to art-world norms. Through projects such as the 2016–17 Why Is Everybody Being So Nice?, he demonstrates outsideness as a relational stance that expands how the curatorial can operate. He urges emerging curators—and the programs that train them—to maintain critical distance from institutional insider behaviors, fostering self-reflexive practices in a field increasingly defined by its own mythologization.

“The art world is shutting down,” a curator friend from New York City recently texted me. As previous art-related certainties crumble—like other aspects of our lives affected by our current and seemingly relentless polycrisis—and funding models increasingly become obsolete, without viable alternatives to replace them, there is an undeniable truth to my friend’s claim. Yet, at the same time, the industries surrounding art’s production, circulation, and speculation through monetization continue to thrive. Evidently, there is no significant slowing down in the organizing of blockbuster exhibitions, biennials, art fairs, conferences, or any other type of international contemporary art event. The same trend can be observed for curatorial activities. The past decades’ mushrooming and current plateauing of curatorial programs across universities and art schools internationally is a case in point.

During exchanges with young curators throughout my tenure as director of the De Appel Curatorial Programme, as a visiting lecturer or critic at various curatorial departments, and in everyday exchanges since then, there is one question that regularly returns. It is the young curator’s equivalent to the young artist’s, “How do I get noticed as an artist? How do I become seen and part of the art world?” For curators, this existential inquiry translates into, “How do I get a job? How do I create opportunities for myself and get inside the art world?” Obviously, such questions are nearly impossible to answer for either group. As has been pointed out exhaustively, there is no such thing as “the art world,” monolithic and singular. There are collaterally bouncing interests, networks, values, politics, ideals, talents, and belief systems, but they fluctuate wildly, depending on what purpose they are being cultivated for, as well as in which geographic context they are situated. Additionally, there are no straightforward formulas available for “getting inside,” as our curatorial reality is increasingly defined by heightened idiosyncrasies and oftentimes mythologized personal trajectories. And what if there is no inside?

Even if a young curator’s concerns about how to get “inside the artworld” are understandable (especially when studying at a curatorial program that costs increasing amounts), it is clearly a flawed goal. To counter such misguided aspirations, I would like to invoke the concept of “outsideness” as a potential position one could explore as a curator, and which is easier to aspire to on an individual rather than an institutional level. It is a term that I borrow freely from the Russian philosopher and literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin and which is applied somewhat mischievously here—the same way in which curatorial practices allow one to freely borrow from art-adjacent theoretical frameworks when conceptualizing exhibitions. For Bakhtin, outsideness refers to the position of the outsider who is always in possession of an “excess of seeing,” by which he means that each of us brings an entirely singular perspective when looking at others, and by extension, at the world. This excess is ethical and relational and allows us to form a more coherent understanding of what we are a part of and what our responsibilities toward others should be.1 Seen as such, shouldn’t outsideness be pivotal to curatorial practice as a whole, and shouldn’t curators always activate this excess of seeing in the activities they engage with? What else is curatorial practice, really? So, instead of tirelessly aiming for the inside, wouldn’t it be altogether more inspiring to consciously and creatively practice outsideness when mounting professional curatorial careers?

Jes Brinch & Henrik Plenge Jakobsen, Ticket booth, 1996, de Appel, Amsterdam. Photo: Niels den Haan.

Looking back at my work as head of De Appel, as well as of its Curatorial Programme, I was confronted by conflicting impulses. The program is a pioneering one globally, second to Le Magasin’s in Grenoble, and by evoking it here, I wish to emphasize its significant place in contemporary curatorial history. For someone who had practiced outsideness extensively throughout his professional activities, leading up to this job, and who didn’t have a formal training as a curator, I suddenly found myself on the very inside of institutionalized curatorial thinking. What made De Appel’s program unique was that one could trace outsideness throughout its rich history. It included such experimental projects as the notorious Crap Shoot, staged by the 1995-96 participants during founder Saskia Bos’s tenure.2 This project tested the boundaries of what is acceptable as curatorial practice altogether. Later decades, however, slowly pushed the Curatorial Programme into the rigid networks of the niche curatorial world. This is not a reflection on the quality of the participants’ output or the ways in which other directors imagined the program, but of the ways in which there appeared to be less and less self-awareness about the functioning of the program and its position vis-à-vis the fluidly defined “art world.”

From within my position, I tried to communicate the necessity of holding on to De Appel’s initial position of outsideness, even though I didn’t necessarily frame it so explicitly to the program’s participants at the time. One of the key elements to achieve this was to consciously steer the participants away from making proper “exhibitions” when developing their collective final project, which was the culmination of the program. This meant avoiding standardized exhibition formats, such as the solo or group presentation, in favor of something more exploratory. In doing this, I tried to (sometimes successfully) convince the participants that they should avoid adhering to established checklists of proper exhibition-making, as these are mostly restrictive and redundant in nature.

The concept of outsideness within the context of my time at De Appel Curatorial Programme translated to suggesting that the participants radically think along with artists, as opposed to focusing on what exhibitions should look like or do, or how they should be mounted or displayed. Instead, I tried to encourage deep collaborations with artists, and to discover what it is that a particular curatorial interest (theirs) could bring to an artist’s practice—in the best cases, advancing both the artistic and curatorial process. More importantly, it was key that these projects would generate purpose within certain discursive settings (which could also be casual), beyond their status as art-related phenomena. One could interpret this as the Bakhtinian excess of seeing of these projects.

Why Is Everybody Being So Nice? Day 4: The Night of Exhaustion and Exuberance. Performance with Arie de Fijter and Ksenia Perek for the Open Avond(S) series, 2017, de Appel, Amsterdam.

A fine example was the 2016-17 Curatorial Programme’s final project, Why Is Everybody Being So Nice?, which was an extensive investigation into the social pressures of niceness, resulting in a four-day program and closing with a collective sleepover, The Night of Exhaustion and Exuberance. Being driven by such (some would say naïve) beliefs in ideas and positions, the curatorial role here was one of outsideness in order to advance a sense of publicness. The curator, then, became more like a humble public servant who bridges the various worlds they/she/he is engaging with rather than producing or safeguarding one—“the art world”—that remains at all times ungraspable and opaque.

Ultimately, what does outsideness mean for university curatorial departments and programs at art schools? I’m not entirely sure. But aren’t they perhaps too focused on fostering a feeling of being inside, of receiving a certain (but not unlimited) amount of privileged wisdom originating from within that you can’t get anywhere else? The problem then is not how to get in, but how to stay out. Or, more precisely, how to cultivate outsideness as a means to enact the curatorial—more like a basic attitude and state of mind that can be achieved from within curatorial sites of learning as well. Evidently, the knowledge and networks they offer are useful as long as one remains conscious of the pitfalls of their potential insularity. Finally, to young curators, I would offer the following thoughts: Don’t rely on institutions too much. Focus on making strong connections with artists and colleagues. Always doubt everything you do, but do it nevertheless. Trust your intuition. Patiently build a singular position of outsideness, carving a world for yourself in deliberate and open ways, instead of adhering to one that is already solidified in curatorial-institutional mythmaking, which might never have existed in the first place.

NOTES

1. Mikhail Bakhtin, “Author and Hero in Aesthetic Activity,” in Art and Answerability: Early Philosophical Essays by M.M. Bakhtin, eds. Michael Holquist and Vadim Liapunov, trans. Vadim Liapunov (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990), 22.

2. Saskia Bos founded the curatorial program in 1994, whereas De Appel itself was founded by Wies Smals in 1975.

-

Niels Van Tomme (he/him) is a curator and lecturer who works internationally at the intersection of contemporary culture and critical social awareness. He was director and chief curator at Argos Centre for Audiovisual Arts in Brussels (2018-24) and De Appel in Amsterdam (2016-18), curator at the Bucharest Biennale 7 (2014-16), visiting curator at the Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture in Baltimore (2011-16), and director of arts and media at Provisions Learning Project in Washington, DC (2008-11). In 2014, Van Tomme received the Vilcek Curatorial Fellowship by the Foundation for a Civil Society for his demonstrated experience and excellence in engaging with international contemporary art.

His exhibitions and programs have been shown internationally, including at The Kitchen (New York), Contemporary Arts Center (New Orleans), Akademie der Künste (Berlin), Tallinn Art Hall (Tallinn), Gallery 400 (Chicago), Värmlands Museum (Karlstad), National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC), and P! (New York). His writings have appeared in Artforum, The Wire, Art in America, Camera Austria, Metropolis M, Afterimage, and Art Papers. His edited volumes include Muntadas: About Academia: Activating Artefacts (2017), Aesthetic Justice: Intersecting Artistic and Moral Perspectives (2015) with Pascal Gielen, Visibility Machines: Harun Farocki and Trevor Paglen (2014), and Where Do We Migrate To? (2011). He has additionally contributed to numerous books and exhibition catalogues, such as Christine Sun Kim: Oh Me Oh My (2024) and Tony Cokes: If UR Reading This It’s 2 Late, Vol. 1-3 (2019). Van Tomme regularly writes about music and occasionally provides liner notes for vinyl records by artists such as Hieroglyphic Being and Aki Onda. He has held teaching positions at Parsons School of Design at The New School (New York) and University of Maryland Baltimore County. He has lectured at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Queen Mary University of London, Vassar College, University at Buffalo, School of Visual Arts (New York), Valand Academy of Art and Design at University of Gothenburg, and the Jan Van Eyck Academy.

Walking & Talking with Tīna Pētersone

Latvian curator Tīna Pētersone speaks about the dynamics and challenges of curatorial practice amid today’s political and social climate in the Baltic countries.

By Tīna Pētersone with Bige Örer

Bige Örer, Tīna Pētersone • 11/17/25

-

Walking & Talking, hosted by Istanbul- and London-based curator and researcher Bige Örer, is a series of video-recorded conversational experiences based on walking with each guest curator in the same location or in two different places in the world. Some of these conversations address broad societal, cultural, or philosophical questions, while others may unfold more intimate concerns and flow with inner journeys. The walks are imagined as poems- collaborative verses composed along a shared path.

In this episode, Örer walks and talks with Latvian curator Tīna Pētersone through the streets of Riga, Latvia. Their focus: the challenges of curatorial practice amid the political and social dynamics in the Baltic countries today, especially in Latvia, emphasizing the need to internationalize curatorial collaborations with other art ecosystems.

-

Tīna Pētersone is a Latvian independent curator with an MFA in Curating from Goldsmiths, University of London.

In 2025, she co-founded the inaugural Riga Art Week and she serves as Creative Producer for Liepāja 2027, European Capital of Culture, where she is developing international contemporary art commissions.

Her practice is shaped by residencies and fellowships across Europe, Africa, and the US: at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris; Hyde Park Art Center in Chicago (CEC ArtsLink, 2022); the Baltic Fellowship at Performa Biennial in New York (2023); the Who Is Being Heard? curatorial program for research across the Nordic region; and the Sisters Hope residency in Copenhagen (2024). She is currently in an academic program, Reframing Colonial Legacies, at Zeppelin University in Friedrichshafen, Germany, and the University of Cape Coast in Cape Coast, Ghana.

Her current work focuses on developing art infrastructures and creating opportunities for artists and art professionals, with particular emphasis on cultural exchanges that connect the Baltics with global artistic communities. -

Bige Örer is an Istanbul- and London-based independent curator and writer dedicated to amplifying the voices and visions of artists. Her curatorial practice is rooted in centering creativity and artistic perspectives, ensuring that artists remain at the heart of every exhibition and project she oversees. From 2008 to 2024, Örer served as the director of the Istanbul Biennial, where she transformed the biennial into a dynamic platform for artistic collaboration and intellectual exchange. She was instrumental in developing programs that broadened the biennial’s reach, particularly focusing on children and youth, while fostering artistic engagement throughout Turkey and internationally. In 2022, Örer curated Once upon a time…, the Füsun Onur exhibition at the Pavilion of Turkey for the 59th Venice Biennale. Her curatorial projects also include Flâneuses (Institut français Istanbul, 2017), an ongoing series involving walks with artists. Örer played a key role in establishing the Istanbul Biennial Production and Research Program, the SaDe Artist Support Fund, and coordinated initiatives such as the Cité des Arts Turkey Workshop Artist Residency Program and the Turkish Pavilion at the International Art and Architecture Exhibitions of the Venice Biennale. Örer has contributed articles to numerous publications and taught at Istanbul Bilgi University. She has also served as a consultant and jury member for various international art institutions, and from 2013 to 2024, she was the vice president of the International Biennial Association. During this time, she also contributed to the editorial and programming board of the association’s journal, PASS. She is a member of the Curatorial Studies Workshop, part of the Expanded Artistic Research Network (EARN).

Poor Space

In schematizing the poor space, the intention is to envision it as a locus of disobedience, ambiguous as well as potentially ambivalent, performing non-totalizing gestures in place of the authoritarian impulse.

By Steven Henry Madoff

In schematizing the poor space, the intention is to envision it as a locus of disobedience, ambiguous as well as potentially ambivalent, performing non-totalizing gestures in place of the authoritarian impulse.

Steven Henry Madoff • 10/21/25

-

Critical Curating is The Curatorial’s section devoted to more theoretically oriented considerations of curatorial research and practice. While of a specialized nature, we seek essays for this section that are written for a broadly engaged intellectual audience interested in curating’s philosophical, historical, aesthetic, political, and social tenets, as well as a labor-based activity and its ramifications.

In this essay, Steven Henry Madoff extrapolates from Hito Steyerl’s notion of the “poor image,” which she proposed in her essay, “In Defense of the Poor Image,” that appeared in e-flux Journal in November 2009. Steyerl wrote about the potential for low-resolution images on the internet to democratize image-making and the global distribution of images (though with caveats). Madoff takes the beneficial character of low resolution as a way to speak about a curatorial strategy that deploys a lack of transparency as a way to address political issues indirectly. He considers related means to accomplish political resistance through redirection, such as the uses of metaphor and allegory, as well as Guy Debord’s notion of the dérive and Edouard Glissant’s promotion of “opacity.” Madoff suggests that such tactical ways of curating may be of increasing importance as authoritarian regimes spread internationally.

This essay, in a different version, was presented as a talk in Riga, Latvia, at the symposium “Eastern European Curatorial Practices: Historical Development and Challenges” held in September 2025.

If this is the new era of artificial intelligence, it’s also the old era, or rather the renewed era, of authoritarianism. Where I come from, New York, the city has never felt more like a bubble in a country whose democracy has never felt more like a punching bag. If Americans are now being shocked on a daily basis by the new regime, we have a lot to learn from Eastern Europe, among other regions of the world, about what is coming, let alone what is here already, and how to respond. And while artificial intelligence is also bringing increasing disruptions to our world, in the context of curating and the wider scope of the curatorial, I can’t say it has made fundamental shifts in the way curators work. Not yet, at least. And so, questions about the impact on the curatorial field under the clouds of authoritarianism, about which Eastern European geopolitics offer historical lessons, are pressing on me as an American, while I certainly have ideas about what technological advancements will bring.

The uproar around AI’s generative image-making and the fear that advanced computation is approaching consciousness and autonomy are as yet unfounded and are, for now, a distraction from the urgent issues of our time, with rising authoritarianism, genocide, climate change, immigration crises, and economic precarity all tipping us toward darkness. I won’t digress further about AI (and yes, there are relatively near-term scenarios in which AI is a baby with a gun), but at the moment it is most practical to say that the ways in which artists and curators are thinking about, producing, and exhibiting algorithmic art are still topical, not truly fundamental to the renovation of our artistic, cultural or political conditions—and, in any case, this kind of work lies along a continuum in an artistic tradition of fascination with machines, not a consciousness of machines fascinated with us.

Still, why I think it’s useful to bring up generative AI image-making here is that its way of shredding and diffusing vast numbers of images to make other images—though, for the most part, visually banal, anodyne, or toxic ones—presents a model of ontological decentering, a collapse of origin, an endless robbery and reshaping that violates and empties authorship yet promises unparalleled possibilities of a democratized and fugitive form of making that links directly to a techno-political condition already diagnosed by Hito Steyerl in her famous 2009 essay, “In Defense of the Poor Image.”1 Steyerl proposed that globally circulated, continually copied and regenerated low-quality digital imagery, while technically degraded and dangerously instrumentalized, also has a high social quotient of democratizing influence, of upgraded mobility, and therefore stands as a political signifier and activator of an alternative political economy—at once low-resolution and high-potential for creative work in the face of hierarchical power.

So, she writes: “The networks in which poor images circulate thus constitute both a platform for a fragile new common interest and a battleground for commercial and national agendas. They contain experimental and artistic material, but also incredible amounts of porn and paranoia. While the territory of poor images allows access to excluded imagery, it is also permeated by the most advanced commodification techniques.” And later in the essay, she concludes: “The circulation of poor images feeds into both capitalist media assembly lines and alternative audiovisual economies. In addition to a lot of confusion and stupefaction, it also possibly creates disruptive movements of thought and affect.”

It seems to me that what she diagnosed with the poor image as an online phenomenon seeping into the world reflects what we have now with AI as a sign of displacement that only amplifies the condition of the poor image and offers a way to think about curatorial work as well. So, let me, for the moment, call it the “poor space” of curating, which has nothing to do with budgets or scale, but as a tactical way of thinking about curatorial making in the stifling atmosphere today of political intimidation and restriction.2 Irony and cunning are the way of the poor space—something I know is familiar to an Eastern European artistic sensibility, while I might also add to this the notion of the dérive, Guy Debord’s Situationist proposition of political parcours, of the roundabout way to get where you want to go as a form of trickster liberation.

Just as the lexicon found in The Curatorial includes the terms “curating” and “the curatorial,” in which “the curatorial” designates a broad conceptual framework for acts of curating—you might say, a socio-political surround in which curating takes place—the “poor space” is a surround for curating in its symbolic mode of misdirection-as-redirection.3 As a token of this idea of the poor space, I think of an image of near-emptiness. The image is of Ryan Gander’s I Need Some Meaning I Can Memorize (The Invisible Pull) (2012), a work that was almost no work at all, consisting of nothing more than a slight breeze in a nearly empty gallery space just to the left as you entered the Fridericianum at the time of Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s documenta (13) in 2012. Along with it, there were four objects, barely noticeable at first: three slender sculptures by Julio González in a narrow vitrine, which had already been installed in the same place at documenta 2 in 1959, and a letter of refusal by Kai Althoff—a participation by refusing to participate that in turn echoed, almost like the breeze in the room, Robert Morris’s actual refusal to participate forty years earlier in documenta 5.

Ryan Gander, I Need Some Meaning I Can Memorize (The Invisible Pull) (2012).

I’d like to use this image as a lever, a curatorial generator to produce a specifically unspecific way in which the curatorial poor space, poor gallery, poor room deploys its subject as a kind of dérive, or what in literature are the devices of metaphor and allegory. Metaphor, as I’ve written elsewhere, affords an artificial pleasure of purposeful distance; it is a way to accommodate ourselves to the brute intractability of the world by shifting appearances.4 At the same time, the allegorical impulse, as Craig Owens noted long ago (and that is instrumental in the activation of the poor space), is restorative through its superimposition of one meaning on another—a form of replacement to empty out the authority it seeks to detour, deflate, deflect, or decline. Allegory, by its substitutive nature, intends to supersede or revoke, but also to make apparent again. Or, as Owens remarks, “In allegorical structure, then, one text is read through another.”5

The emptiness that Gander’s work deploys also carries the ghost of another moment in the history of art that speaks in the language of metaphor and allegory in order to insulate itself, to rebuff and ironize governmental oppression: the moment of the Moscow Conceptualists in the 1970s and ’80s as the Soviet Union slowly ran its great ship into the shoals of its exhaustion. So, Ilya Kabakov wrote about the local art of his contemporaries: “This contiguity, closeness, touchingness, contact with nothing, emptiness makes up, we feel, the basic peculiarity of ‘Russian conceptualism’... It is like something that hangs in the air, a self-reliant thing, like a fantastic construction, connected to nothing, with its roots in nothing...”6 Kabakov’s work, along with those of Komar and Melamid, Irina Nakhova, and others, through slogans, paintings, and installations, addressed the voice of monolithic Soviet inflationary self-regard to satirize, allegorize, puncture, and relieve it of its authority. If a famous work by Kabakov, his 1989 allegorical installation titled The Man Who Flew into Space from his Apartment, is the material opposite of Gander’s empty room, presenting a mad overload of propagandist images that symbolize the burden of Soviet life, they are both imaginaries of escape from oppressive weight.

Ilya Kabakov, The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment, 1985, mixed media, installation view, 2017. Photo: Andrew Dunkley.

This mode of desolidification through metaphor and allegory, through an emptiness that is not, is emblematic of what the poor space offers, shifting the blunt facts of the world through symbolic relations. They do so precisely to bring us around from another side, a dérive. George Orwell wrote in his 1946 essay, “Politics and the English Language,” that writing politically may “vary from party to party, but [it is] all alike in that one almost never finds in [it] a fresh, vivid, home-made turn of speech.”7 Yet the value of the poor space is its curatorial status as a platform that reorients and re-presents, often in a local register, and that, as with allegory’s implicit humor, slyness, ironies, and slipperiness, illuminates ways around the politics of oppression and displacement by way of displacement, bringing something vivid and fresh.

The very idea of a situated form of expression that deploys oblique means toward a revised and revived language of critique is recalled in other Eastern European actions, particularly what have been called “monstrations,” as Zdenka Badovinac recounts in her book, Unannounced Voices: Curatorial Practice and Changing Institutions. There, she notes Andrei Monastyrsky’s Collective Actions Group, active from the mid-1970s, along with the Russian philosopher Alexei Yurchak’s reflections on the Slovenian art collective Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK), begun in the 1980s. In relation to NSK’s work, he speaks of “monstrations”—a word that conflates “demonstration” and “monsters”—and he remarks that “participants in monstrations carry signs with apparently ‘absurd, meaningless and disconnected slogans.’” Wonderfully off-kilter examples include: “We support same-sex fights” and “I demand meaningful slogans.” These forms of performative illogic illustrate a rhetorical strategy that, as an artistic and curatorial action, seems at first “utterly apolitical and nothing more than a meaningful carnival,” as Yurchak observes. “However, the closer scrutiny shows that monstrations [are] a powerful form of political critique in the context of late-Putin rule.”8

Collective Actions Group, Slogan (January 26, 1977). The text reads: “I DO NOT COMPLAIN ABOUT ANYTHING AND I ALMOST LIKE IT HERE, ALTHOUGH I HAVE NEVER BEEN HERE BEFORE AND KNOW NOTHING ABOUT THIS PLACE.” A quote from Andrei Monastyrski’s 1976 poem, “Nothing Happens,” a key text for the Moscow Conceptualists.

Such performative renderings exemplify the ambitions of the poor space to wriggle free from the vise of authoritarian restrictions by means of linguistic and apparently counter-rational modes of expression—a vividness accomplished through illegibility and deracination. The poor space is not fixed in its location, and it is intellectually permeable. It doesn’t necessarily seek reparations so much as it reroutes the rhetorical bounds of the regime, disarticulating its elocutions of power. The poor space isn’t necessarily about or driven by collectivity, but it is, by shrewdness and perhaps at times by luck, a space of infection and, therefore, of democratizing distribution. It offers the possibility, in Gayatri Spivak’s phrase, of “affirmative sabotage.”

In this regard of artistic and curatorial moves of misdirection-as-redirection, of illicitness, of willful illegibility in the face of juridical scrutiny, I think as well of Philippe Pirotte’s Montreal Biennale in 2016, into which he curated Corey McCorkle’s Monument (2013), a video projection of a blind horse that could only be viewed in the dark and at night, the constraint on seeing proposed as a way to perceive against the odds, against the grain. Empathy, or imaginary transfer, from one housing of perception, the blind horse, to another, the human, encourages this action, performing this nightshift that proposes another way to see out of need.

Corey McCorkle, Monument, 2013, HD projection, 5 min., 36 sec., Montréal Biennale, 2016, at La Station, former gasoline station designed by Mies Van der Rohe, Ile des Soeurs, Montréal.

Following directly from the tension of this nocturnal frame of emancipatory obliqueness, there is Pirotte’s Busan Biennale last year to consider. Titled Seeing in the Dark, its basic premise was this sidelong approach to political address as a form of deviation and cunning. One example of this was Pirotte’s inclusion of the work Hail (2020), by Lee Yanghee, picturing South Korea’s underground rave scene in the early 2000s and calling up metaphors of formal and alternative dance, altered archetypes, queerness, and bodily pleasure that countermands public restriction.

Lee Yanghee, Hail, 2020, 4-channel video, 6-channel audio, 15 min., 46 sec., Busan Biennale, “Seeing in the Dark,” 2024.

Of course, writing this within the context of Eastern European cultural-political practices, it is all too clear that there is a need for strategies of the dark, so to speak; for a rhetorical commons of the oblique; an artistic economy dedicated to gestures of displacement that can thrive in the shadows of authoritarianism as a means of survival, or what Judith Butler has spoken of as the will to “to minimize the unlivability of lives,” which, once again, is our current challenge.9

What the use of the term “poor space” helps me to emphasize is that an exhibition made with this kind of strategy usefully decenters its subject, shifting authoritarian gravity, and just as Pirotte did in Busan, it wears the cloak of Édouard Glissant’s idea of opacity as resistance, as beneficial ambiguity.10 As well, this is what the political theorist James Scott noted in his idea of the public transcript and the hidden transcript, where the public transcript is visible and therefore can be controlled, shut down, even erased, while the hidden transcript is illicit, mobile, subversive.11 And in turn, opacity and the hidden transcript echo in Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s proposition of “fugitive planning,” about which they write: “To enter this space is to inhabit the ruptural and enraptured disclosure of the commons that fugitive enlightenment enacts.”12 Those words perfectly correspond with Steyerl’s claim that the poor image “creates disruptive movements of thought and affect.”

Zasha Colah, in her 2025 curation of the Berlin Biennale, invoked a similar dérive, titling her exhibition “passing the fugitive on,” taking the figure of foxes shifting through the cityscape of Berlin as a tutelary spirit under the siege of contemporary life that symbolizes, as she put it, “the cultural ability of a work of art to set its own laws, in the face of lawful violence.”13 She calls this, as an active verb, “foxing,” and speaks of these moves as a fugitive way, a potent illegality, that traverses injustice. Of course, not every proclamation of rebellious fugitivity is successful, and the structural contradictions of a government-funded “foxing” exhibition in Germany, with the imposition that some subjects cannot be discussed (and weren’t), complicates and diminishes any actual action intended to outfox those very restraints.

Berlin Biennale logo, 2025.

Nonetheless, in schematizing the poor space, the intention is to envision it as a locus of disobedience, one that may well be both ambiguous and ambivalent, performing non-totalizing gestures in place of the authoritarian impulse. This helps us to see that the counter-narrative of the poor space is one of recalibration and disequilibration by intention, a rhetoric of sleight-of-hand, an allegorical revision that may adumbrate, that may whisper almost inaudibly its truth to power, throwing its voice as political ventriloquism. Needless to say, this may be increasingly useful as a curatorial tactic, certainly in the US, but of course in so many other places today.

I’m not suggesting this is the only political form of curating. There are other, surely more frontal, curatorial approaches toward resistance, reform, repair, reparation, and community. But the poor space as a cunning form of shifted thought, as a curatorial platform that embodies disembodiment and an altered political situatedness, is a strategic push against the force, the high resolution, of authoritarianism, in order to turn it—like Ryan Gander’s Invisible Pull—into an ungraspable breeze that’s nonetheless felt; to turn the poor space and its particular form of low resolution into a liberatory instrument of fugitive enunciations.

Ryan Gander, I Need Some Meaning I Can Memorize (The Invisible Pull) (2012).

NOTES

1. Hito Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image,” e-flux Journal, number 10 (November 2009), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image.

2. I should note that the poor space that I speak about here is predominantly envisioned as a physical space in which physical exhibitions are staged. But, of course, the poor space can be virtual and accessed through such technological devices as a computer, a mobile phone, or a spatial computing device, such as a VR headset or smart glasses. The poor space accommodates many spatialities and temporalities.

3. See https://www.thecuratorial.net/index/lexicon/curating-swbk8.

4. Steven Henry Madoff, “Metaphor and the Feeling of Fact,” The Brooklyn Rail, October 2013, https://brooklynrail.org/2013/10/criticspage/metaphor-and-the-feeling-of-fact/.

5. Craig Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism,” October 12 (Spring 1980): 69.

6. Ilya Kabakov, as quoted in Mikhail N. Epstein, After the Future: The Paradoxes of Postmodernism and Contemporary Russian Culture, trans. Anesa Miller-Pogacar (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1995), 188.

7. George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language,” The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, volume 4, eds. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1968), 135.

8. See Zdenka Badovinac, Unannounced Voices: Curatorial Practice and Changing Institutions (London: Sternberg Press, 2022), 34.

9. Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 67.

10. Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997).

11. James C. Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985).

12. Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Wivenhoe, UK: Minor Compositions, 2013), 28.

13. See https://www.berlinbiennale.de/en/biennalen/3389/13th-berlin-biennale-for-contemporary-art.

-

Steven Henry Madoff is the founding chair of the MA Curatorial Practice program at the School of Visual Arts in New York and editor in chief of The Curatorial. Previously, he served as senior critic at Yale University’s School of Art. He lectures internationally on such subjects as the history of interdisciplinary art, contemporary art, curatorial practice, and art pedagogy. He has served as executive editor of ARTnews magazine and as president and editorial director of AltaCultura, a project of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. His books include Unseparate: Modernism, Interdisciplinary Art, and Network Aesthetics from Stanford University Press; Thoughts on Curating from Sternberg Press (series editor); Turning Points: Responsive Pedagogies in Studio Art Education (contributor) from Teachers College Press; Learning by Curating: Current Trajectories in Critical Curatorial Education (contributor) from Vector; Fabricating Publics (contributor) from Open Humanities Press; What about Activism? (editor) from Sternberg Press; Handbook for Artistic Research Education (contributor) from SHARE; Art School (Propositions for the 21st Century) (editor) from MIT Press; Pop Art: A Critical History (editor) from University of California Press; Christopher Wilmarth: Light and Gravity from Princeton University; To Seminar (contributor) from Metropolis M Books; and After the Educational Turn: Critical Art Pedagogies and Decolonialism (contributor) from Black Dog Press. Essays concerning pedagogy and philosophy have appeared in volumes associated with conferences at art academies in Beijing, Paris, Utrecht, and Gothenburg. He has written monographic essays on various artists, such as Marina Abramović, Georg Baselitz, Ann Hamilton, Rebecca Horn, Y. Z. Kami, Shirin Neshat, and Kimsooja, for museums and art institutions around the world. His criticism and journalism have been translated into many languages and appeared regularly in such publications as the New York Times, Time magazine, Artforum, Art in America, Tate Etc., as well as in ARTnews and Modern Painters, where he has also served as a contributing editor. He has curated exhibitions internationally over the last 35 years in the United States, Europe, and the Middle East. Most recently, Y.Z. Kami: In a Silent Way at MUSAC, León, Spain, June 2022-January 2023. Madoff is the recipient of numerous awards, including from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Academy of American Poets. He is a member of the Curatorial Studies Workshop, part of the Expanded Artistic Research Network (EARN).

Thoughts on Repair and Remediation

Remediation is not nostalgia, nor is it a utopian projection. It is work performed and actualized, always oriented toward the present and the possible futures that emerge from it.

By Daniela Zyman

Remediation is not nostalgia, nor is it a utopian projection. It is work performed and actualized, always oriented toward the present and the possible futures that emerge from it.

Daniela Zyman • 10/10/25

-

Critical Curating is The Curatorial’s section devoted to more theoretically oriented considerations of curatorial research and practice. While of a specialized nature, we seek essays for this section that are written for a broadly engaged intellectual audience interested in curating’s philosophical, historical, aesthetic, political, and social tenets, as well as a labor-based activity and its ramifications.

In “Thoughts on Repair and Remediation,” Daniela Zyman examines the possibilities and limitations of repair as both a concept and a practice, drawing from her curatorial work with Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary (TBA21) at C3A, the Andalusian cultural institution in Córdoba. Anchored in a trilogy of exhibitions—Abundant Futures, Remedios, and The Ecologies of Peace—the essay reframes remediation not as a return to a prior state, but as an ongoing, situated engagement with brokenness, violence, and loss. Engaging with Indigenous cosmologies, Black radical thought, and postcolonial critique, Zyman approaches repair as a collective, relational, and necessarily unfinished process. Rejecting redemptive narratives, she argues for a politics and “poethics” that remain with the trouble, embracing the ambivalence and irresolution inherent in reparative work. She further situates contemporary remedial praxis within planetary struggles for habitability in the ruins of extractive capitalism and settler modernity.

The essay originally appeared in Spanish in Remedios / Ecologías De La Paz, edited by Alex Martin Rod and Zyman (Madrid: Turner Ediciones, S.A, TBA21, 2025).

In 2022, TBA21 was invited to develop an exhibition trilogy at the C3A Centro de Creación Contemporánea de Andalucía, marking a three-year institutional residency in Córdoba. This collaboration sought to situate and contextualize visionary artistic practices from the TBA21 collection within the context of its longstanding engagement with ecological and social concerns. The three annual exhibitions in TBA21’s cycle that I curated at C3A—conceived around the concepts of abundance (Abundant Futures), repair (Remedios), and just and peaceful futures (The Ecologies of Peace)—experimented with artistic expressions and aesthetic methodologies dedicated to the collective struggle of forging a livable imaginary for the future. They were not only curatorial articulations but also propositions for how to endure and create under conditions of crisis. As the anthropologist Elizabeth A. Povinelli reminds us—drawing on the wisdom of her Aboriginal family in Australia—this requires what she calls a “science of dwelling.”1

Such a science refuses to treat catastrophe as an external condition, instead transforming loss and grief into meaningful actions and aesthetically resonant creations through which individuals shape more-than-human and storied realities. It insists that enthusiasm for worldmaking must not be abandoned in the face of deprivation and dispossession. And rather than being paralyzed by the desire to restore a previous condition, this science cultivates relational ways of being and thriving under the (failing, hostile, and sad) conditions that humans must contend with, passing down the ingenuity and wisdom for their rehabilitation to future generations.

Consequently, the science of dwelling in economies of abandonment doesn’t imply acceptance of the status quo, or some sort of gratitude for the (limiting and always limited) possibilities that remain. This science is not misguided by the artistic and scientific canons that no longer extend comfortably to the contemporary situation. Instead, it urges us to consider new ideas and models for a different geology, an epoch that demands that we experiment with our cosmologies, concepts, stories, and with everything broken and damaged. It unleashes creativity through encounters and draws very near the objects we study, relate to, or wonder about—a closeness that can be described as intimacy or situatedness, or simply as being touched. This closeness is fundamental for building relationships based on relational accountability, steering us away from extractive economies and reductive ways of knowing, which dictate and limit the shape of our world.

We also draw inspiration from the many transformative movements, initiatives, and engagements that have emerged over the last few decades, including—but not limited to—those centered around buen vivir, radical agri-ecologies, the reinvigoration of the commons, economic degrowth, care networks, abolitionism, peace activism, and the Black, Brown, Indigenous, and youth movements marching in the streets to demand an earth uprising. This inspiration also extends to the many artists, researchers, and curators who have mined and recomposed the archives and counter-archives of abundance, repair, and justice.

Reparative Politics under the Climates of Capital

In everyday language, the term “remediation” can encompass meanings like “remedy,” “repair,” “fix,” “renovate,” “restore,” or even “return.” It can also extend to practices of healing, reparation, and restitution. However, these broad interpretations can lead to confusion unless we clarify where our emphasis lies. Each synonym offers distinct insights but also has its limitations. To navigate this complexity, let’s begin by exploring the concept of Remedios as a form of reparative politics. The first lesson, as I see it, is this: the creative ethics of repair are neither an individualistic pursuit of self-improvement nor a narrow, single-issue concern. Rather, it encompasses a range of social, material, and symbolic practices that address multiple, intersecting breakages or crises.

Indeed, the call for reparative politics runs deep in a time marked by numerous crises and the call for atonement and re-memorialization of past injustices. If the spirit of revolution defined the generation of the 1960s and beyond, today’s political engagements tend toward reparation, healing, and reconciliation. The most radical visions and corrective actions converge on addressing the damage to the environment, defending a different concept of the human and the health and well-being of earthly life, while redressing the aftermath of colonialism and its genocidal and epistemocidal impulses. Guided by the understanding that the social, political, environmental, and epistemic crises (understood as a turning point, per the word’s Greek etymology) are interrelated, with their effects compounding, thinkers, artists, and activists often rally under a trans-environmentalist banner, which to political thinker Nancy Fraser includes both “‘environmental’ and ‘non-environmental’” facets of the crisis.2

The “climates of capital,” as Fraser calls the confluence of ills and afflictions bestowed on the world through global capital, are as disruptive and pervasive as the weather. Rather than unifying “the world” through more mobility, exchange, and commercial integration, globalization’s forbidding paradox has been the production of more discord, fragmentation, and injustice. The primary motivation that has driven the neoliberal world order has been “the reallocation of the Earth's resources and their privatization by those who had the greatest military might and the largest technological advantages,” according to the Cameroonian political scientist Achille Mbembe.3 The machinations of primitive accumulation have not only accelerated inequality among nations and inflicted an unparalleled environmental catastrophe on the biosphere but also escalated a supremacist and deeply racist anti-humanism, premised on the notion that the world belongs to a few exceptional groups.

The exclusion of racialized, poor, differently abled, and otherwise stigmatized groups— “human bodies deemed either in excess, unwanted, illegal, dispensable or superfluous”—from the world in common is driven by a white, supremacist “politics of belonging” on the rise since the 1990s.4 These politics of belonging are triggered by an identitarian conception of selfhood and “defensive identity,”5 rooted in the complete disregard and lack of empathy for the rights, lives, and well-being of those deemed outside the boundaries that differentiate and often physically separate those who belong from those who do not.6 Such forces and powers invest in building walls and borders to police the movement and determine the rights of those who must be excluded. And they celebrate the individual (and by extension propertied relations) as the model of the human, whose self-aggrandizing entitlement to freedom, sovereignty, possession, aggressive self-expression, self-defense, etc., undermines social obligation, solidarity, and sociality.

It is precisely the divisionary impetus of both globalism and identitarian politics that we must resist through reparative ethics. Even in light of the different agendas of environmentalist movements, Indigenous struggles, social mobilization, and anti-capitalist activists, among others, it is only, as Fraser aptly demonstrates, a unified politics that links ecological concerns with social justice movements that can lead to the transformation of the economic, political, and epistemic systems that underpin it. This means building alliances between environmentalists, labor movements, and social justice advocates to create more equitable and sustainable futures.

No Quick Fix

Perhaps the most contested interpretation of Remedios is the act of fixing something broken—broken earth, broken bodies, objects, ideas, infrastructures, or even a broken world. Given the current dismal state of affairs, the act of fixing would seem like a noble pursuit. But what if, as the unfolding climate catastrophe lays bare, there are things that are irreparable or broken beyond repair? What if that which we try to mend and plaster over are merely the symptoms or small structural parts of much larger infrastructures of brokenness? Black, Brown, and queer theorists and writers, whose “lives are lived under occupation,” have been developing a rich body of thinking on repair, heedful of the material and immaterial injustices of colonial violence that persist into the present.7

The Black poet and writer Fred Moten, who has much to offer for understanding the genocidal structures of slavery and how they are currently active in racial capitalism, argues that the scars and losses from these violations are neither reducible nor fixable. He states: “To imagine that our stories of loss are also stories of war is also to imagine that there will be no repair, that this is something we’ll never get over, and that this not getting over it, which will have always been part inability and part refusal, bears so much more than the limited possibilities that repair implies.”8

Moten challenges us to consider the im/possibility of repair, suggesting that enduring wounds and losses may not be something to “fix,” but rather stories of war to share and reckon with. He does not explicitly write, though that’s what I understand, that these acts of sharing—through writing, reading, storytelling, and art-making—must refuse more harm or injury in the name of reparation.9 Given that the urge for repair is potentially reactionary and sometimes extractive, certainly damage-centered and quite often reductionist, only the “practice [of] vigilance, militance, and love, which (the abolition of) war demands” would lay the groundwork for a future where racism— understood as the systemic vulnerability to premature death—is no longer tolerated as the foundation of our existence.

Similarly, for the French-Algerian artist Kader Attia, the traumas of history’s darkest moments have left enduring material and immaterial scars, much like a phantom limb from an amputated body part.10 In his art, Attia attends to the work of repair by exposing the brokenness of things and holding their shards in place with visible staples. Metal clips and clamps serve as both evidence of the endured violence and a starting point for the ongoing and often denied process of healing. To Attia, “fixing” means “to hold in place,” allowing the fractures and amputations to continuously unmoor the beholders, with his art persistently asking more questions, or as poet Ross Gay puts it, “unfixing” us—that is, unsettling and unworlding us.

As we are bound to live with the consequences of irreparability, recognizing that repair always already arises amid a rolling catastrophe, and acknowledging that something ongoing cannot be memorialized, we have to concede that any form of collective ameliorative efforts and remediation would have to summon their energies from the residues, wounds, and debris left behind—from the underside of history. The conditions of brokenness are only bearable if they are seen not through the hope for benevolent acts of repair, but through the intimate and intricate relationships inherent in the science of dwelling, which, as discussed, is both an analytics and a worldview in action, responding to the unfolding politics of abandonment. It is in the terraformed and depleted soil where seeds are planted and new growth is nurtured. Working with broken tools, inadequate and rigged, is unsettling, humbling, and sobering. It puts us to the task of cobbling things together, improvising with what we have, while grieving losses and tending to wounds. On a geologically and biologically destabilized planet, this entails acknowledging and listening to the vexed forces that have been silenced and are now revendicated in their presence.

With this sobering realization comes another difficult junction in the face of vulnerability. Given the current conditions of life, where no spaces are untouched by conflict, residual traces of dispossession, or the stench of environmental degradation, reparative work cannot withdraw into safe spaces. Safe spaces are bordered and defensive, often built on one-dimensional notions of identity, subjectivity, and entitlement. While striving for solidarity, mutual support, and communal bonding is imperative, immunity (which has its root in the term munus, the public duty or service offered to the communis) has exclusionary effects due to its overemphasis on security and defense mechanisms. The same holds true for art institutions. If art spaces pretend to offer zones of comfort and embrace an exclusive and at times elitist politics of intimacy that serve as antidotes to otherwise complex and painful realities, they risk replicating a logic of enclosure. Under the contemporary regime of bordering, cultural spaces that prioritize protection and immunity often end up reinforcing divisions, excluding those considered insufficiently radical.

The Political in Our Time Must Start from the Imperative to Reconstruct the World in Common11

If repair (as the act of fixing) is im/possible, beyond our best intentions, can we nevertheless aspire to “reconstruct the world in common”? This concept of reconstruction is not about creating something new, but rather about interrupting the cycles of destruction and undoing that characterize modern life and the kinds of pro-capital counter-reforms of extractivism and structural adjustments. Mbembe considers reparation and restitution as the only viable politics for creating conditions under which individuals and their world can sustain their presence. Despite the difficulties of repair and its potential failure, Mbembe focuses on ways to restore relationships and livability, allowing for the renewal of shared experiences and alliances in a world that is caught up in the contradictions, injustices, and structures that we have already identified as violent, damaged, and intolerable. He is remarkably emphatic when he states: “The key question today is how (life and the world in common) can be repaired, reproduced, sustained and cared for, made durable, preserved and universally shared, and under what conditions it ends.”12

In the epilogue to his influential book Critique of Black Reason, Mbembe identifies the life-sustaining “endless labor of reparation”13 within African cosmologies and vernacular knowledge, whose function was to negotiate and consolidate the relationship between humans and the earth beings with whom they share the world.14 Initiated experts (akin to Amazonian shamans or magicians in other cultures) were and are, in a sense, “reality therapists,” whose labor is to harmonize the effects of transformation with processes of regeneration. As long as the curative work on the cosmological system is performed, life stabilizes in an “imperishable form” that strives toward reproduction and multiplication. “Sharing the world with other beings was the ultimate debt,” Mbembe concludes.15

It is neither nostalgia nor traditionalism that motivates Mbembe. Like Moten, Denise Ferreira da Silva, and other thinkers, he insists that the therapeutic interventions needed today must deeply engage with the erasures and the cannibalistic structures passed down from modernity. Under the ominous climate regime of the Anthropocene and amid the ruins of racial capitalism—potentially even hurtling “toward the End of the World as we know it”—reparation must address the catastrophic impacts of systemic, historical, and ongoing violence and destruction wrought by colonialism and capitalism (including relentless growth, consumption, extraction, exploitation, and dispossession).16 To build a world that we share, Mbembe insists, “we must restore the humanity stolen from those who have historically been subjected to processes of abstraction and objectification. From this perspective, the concept of reparation is not only an economic project but also a process of reassembling amputated parts, repairing broken links, relaunching the forms of reciprocity.”17

Most importantly, Mbembe’s reference to precolonial healing practices points to an elemental aspect of reconstruction: the inseparability of reparation from everything related to the land. Throughout the Indigenous world, any science of dwelling is rooted in land relations, as are Indigenous legal regimes, theories, stories, and the kinship relations to other earthly beings. (And as is colonialism, by definition, the access to land for settlement and extraction.) To specify the meaning of land for Indigenous relations, Robin Wall Kimmerer writes that it is “everything: identity, the connection to our ancestors, the home of our nonhuman kinfolk, our pharmacy, our library, the source of all that sustains us. Our lands were where our responsibility to the world [was] enacted.”18

Land relations are not metaphorical; they are fundamentally methodological. They are methodological inasmuch as they assert the inseparability of bodies and lifeworlds while actively enacting protocols that do not “moralize maximum use, universalize, separate, produce property, produce difference, maintain whiteness.”19 These relations refuse metaphorical and compensatory gestures that fail to dismantle exclusionary spatial arrangements designed to sustain settler futures. And while they are specific to peoples and lands, their scope is planetary and in solidarity against ongoing dispossession, thus fostering cooperation among the incommensurabilities of different worlds, values, and obligations.

The struggle to reconstruct the common world lies in navigating the persistent and compromised afterlife of spoilage and the reweaving of palliative and nourishing relations. It creates an intrinsic ambivalence that we must tolerate and integrate into our work. Reparative interventions in art and transformative politics blend the soothing and ameliorative powers of aesthetics and “poethics” with the acknowledgment of the “total violence,” according to Ferreira da Silva, which threatens the durability of the world as we know it.20 This form of practice thrives on the tension between critical reckoning and “radical hope,” focusing on channeling these complex and antagonistic emotions rather than seeking mere redemption or immunity.

No Return to a Pristine Past

There is one other fallacy I would like to address when considering reparative effects on existing and future worlds. While reparation is multitemporal and originates in history, it cannot offer a path for returning to the past or any (mythical) wholeness. From the many concepts often used somewhat interchangeably to describe the ethics of repair, terms like “restore” and “renovate” imply efforts to reclaim a prior state or condition, grounded in ideals of how things should be founded on a past often imagined from the present perspective. In fact, the root of the word “renovation” is novus, indicating a process of making something new again.