The Sovereign Fox Persuades Law to Dissolve into Politics

The juridical ambitions of Zasha Colah for her edition of the biennale were laudable, but elusive as her symbolic fox.

By Sophie Barfod

The juridical ambitions of Zasha Colah for her edition of the Biennale were laudable, but as elusive as her symbolic fox.

Sophie Barfod • 1/23/25

passing the fugitive on, 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, Berlin, June 14 – September 14, 2025

-

On Site is The Curatorial’s section in which writers review exhibitions from a curatorial perspective—not an art review, a curatorial review. This is also a showcase for master’s degree students in the MA Curatorial Practice program at the School of Visual Arts (the home of the journal) to publish as part of the program—though others are welcome to write for On Site as well.

In this review, Sophie Barfod examines the 13th Berlin Biennale, passing the fugitive on (2025), curated by Zasha Colah, focusing on its use of dramaturgy to frame law, justice, and activism. Structured as a dispersed performance in which viewers are cast as jurors and artworks function as evidence, the Biennale presents law as mutable and performative, gesturing toward fugitivity as an ethical response to lawful violence. Barfod critically evaluates how this approach engages Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL), historical instances of immoral legality, and contemporary artistic practices that destabilize juridical authority, ultimately arguing that the exhibition’s reliance on ambiguity functions as a protective curatorial condition.

Zasha Colah cast her Berlin Biennale, titled passing the fugitive on (June 14–September 14, 2025), as a kind of performance theater spread among four different locations. The drama inherent in using performance theater as a curatorial approach seems an effective attempt to draw in contemporary (often attentionless) art viewers. To that end, the Biennale presented sixty artists and more than one hundred seventy works of art, intending to stimulate a debate on how to position oneself in relation to repressive contexts. Criticism has arisen about the irony of curating a show that apparently seeks justice, while “the viewer is invited to think about almost everywhere but Gaza.”1 It has been argued that the Biennale gravitated toward safer forms of activism, operating within what critics have described as a frame of complicit silence. The Biennale chose to omit geopolitical contexts where global demands for justice continue to be most pressing, therefore aligning itself with sites of political power that prefer such conflicts to remain unspoken.2 This essay examines how justice is articulated curatorially and asks whether legal questions framed through implicit dramaturgy can sustain an activist claim under conditions of political urgency.

Artcom Platform stages a silent monument commemorating the individuals in Kazakhstan who were killed, detained or tortured in 2022 in the uprising known as “Bloody January.” Image: Elisa Carollo.

Colah’s exhibition as a construct operates within the register of the performative, in which passing the fugitive on employs dramaturgy as the primary curatorial intervention. Dramaturgy is traditionally examined curatorially through the ways in which a theatrical setting opposes the standard white cube as a site for display. Even though the Biennale employed scenographic strategies—such as the black-box theater exhibition room at the Hamburger Bahnhof—its staging more generally functioned as a forum for judgment, in which meaning was produced through assigned roles and procedural relations rather than through the white-cube logic of autonomous aesthetic experience.3 Visitors were cast as a public jury, artworks functioned as evidence, and the curatorial framework assumed the position of a closing argument. Such role assignment exceeds metaphor and enters the logic of juridical theater, where interpretation is inseparable from performance. The exhibition space becomes a stage on which judgment is rehearsed rather than resolved. This reveals the risk embedded in this approach: moral interpretation grants judges—and here, viewers—a wide margin for discretion, opening the door to judicial overreach. By asking the audience to “judge the judge,” Colah foregrounds law as a malleable construct, one that is subject to performance and perception. Authority shifts from the institution to the individual, where the viewer becomes the arbiter of moral principles. Some argue that legal interpretation, whether within legal institutions or artistic contexts, is ultimately dependent on collective belief, meaning it is ideological and subject to biases. In the Biennale, Colah seems to shift legal interpretation from legal institutions to aesthetic and social performances, allowing its audience to reflect on their own biases and beliefs in relation to morality.

The Biennale’s central motif is the fugitive fox, a creature that does not break laws but lives indifferently to them. Hence the title, passing the fugitive on: an instruction to carry evidence in body and memory until the right moment to relay it.4 Colah uses the imagery of the fox to pass the idea of fugitivity on to others as an activist gesture and ambition. In the catalogue, she defines this state as the cultural capacity of art to set its own laws in the face of lawful violence, moving outside the law’s demand to be acknowledged. What Colah presents, then, is not merely the fact that law is interpreted, but the possibility of a different horizon for justice, one in which legality gives way to justified resistance and social struggle. Here she converges with the legal movement called Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL), which reframes justice as an ongoing negotiation that takes into account colonial histories, structural asymmetries, and the voices of the marginalized. Critics of TWAIL argue that framing justice as “struggle” or “resistance” risks being too open-ended. If justice is always contested, what are the concrete standards? How do we know when justice is achieved or when resistance itself becomes oppressive?5

The former courthouse on Lehrter Straße, 2025. Image: Raise Galofre.

Colah aims to answer this question with the Biennale’s exhibition section titled “Legality, Illegality, and the Artist’s Claim,” set in the former courthouse on Lehrter Straße. Colah utilizes the site itself as a curatorial argument by excavating the building’s history, as it was the site of the 1916 trial of the German socialist politician and anti-war revolutionary Karl Liebknecht. Prosecuted under wartime censorship laws for his participation in anti-war demonstrations and his criticism of the German military, Liebknecht was a key figure in debate on immoral legality. As the only member of the German parliament to openly oppose the country’s involvement in the First World War, his stance on anti-militarism marked a significant rupture within the legal order.6 Colah mobilizes this legacy by framing the exhibition vis-à-vis this conflict, which was later widely read as unjust. She treats the building less as a neutral container than as an archive of historical institutional immorality. Yet this curatorial precision risks evaporating at the level of encounter. If the historical hinge is legible only in the catalogue, then the exhibition’s ethics remain essentially invisible. For a project that leans on dramaturgy, that’s a structural inconsistency: the trial’s “whispers” should have been staged as part of the exhibition’s script, materialized through some form of scenography or explicit interpretive cues, so that the viewer meets the curatorial argument in space.

Simon Wachmuth’s work plays into this eerie sense of legal injustice with his video commission From Heaven High (2025). In the first half of the work, a black-and-white performance confronts the viewer with the figure of a marching, literally pig-headed soldier at Tempelhofer Feld, where the stark imagery is juxtaposed with Martin Luther’s sacred hymn, “Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her” (From Heaven High I Come). Once repurposed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to support German imperial ambitions, the hymn’s inclusion highlights how cultural symbols have historically been used to sacralize the state and advance nationalist agendas.

Simon Wachsmuth, From Heaven High, 2025, installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, former courthouse on Lehrter Straße, 2025. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025; Zilberman Berlin/Istanbul. Image: Eberle & Eisfeld.

Wachmuth uses this once-sacred hymn to critique the myth of neutrality in cultural heritage, and instead creates a sinister scene concerned with (in)justice. Marching—once a sign of discipline and unity—now becomes a symbol of militarism as performative theater. Wachmuth extends this theatricality into the courtroom that’s shown in the second half of the video, where the logic of militarism is ridiculed further. He presents the scene of a trial as a dramatically lit space in which the very notion of impartiality is replaced by the theatrics of the judge, who declares: “I’ll decide who’s bad and who gets sentenced.” The sovereign tone projects authoritarian overreach, signaling how personal (im)moral judgment, not law, guides decisions. Wachmuth uses this allegory to critique creeping authoritarianism and the erosion of democratic safeguards, hinting at “rule by man, not the law.”7

From Heaven High illustrates the way unlawful directives can issue from the law, calling the very grounding of the law as “blind justice” into question. The work draws on John Heartfield and Rudolf Schlichter’s 1920 Dada installation, Prussian Archangel, at the International Dada Fair in Berlin. It featured a pig-headed papier-mâché soldier with a wire-mesh body hanging from the ceiling, responding to the dubious moral righteousness of military (Prussian) officers in the wake of the disasters of the First World War.8 The original work included an absurd instruction that mirrored the absurdity of war logic, stating that “to fully comprehend this work of art, one should exercise for twelve hours a day on the Tempelhofer Feld with a fully packed backpack and equipped for a field march.” This satirical directive mimics Dada’s anti-war stance, and Wachmuth takes the absurdity of obedience to nationalism as a crude practice at the hands of pigs (sorry, pigs!) and enacts it in his video.

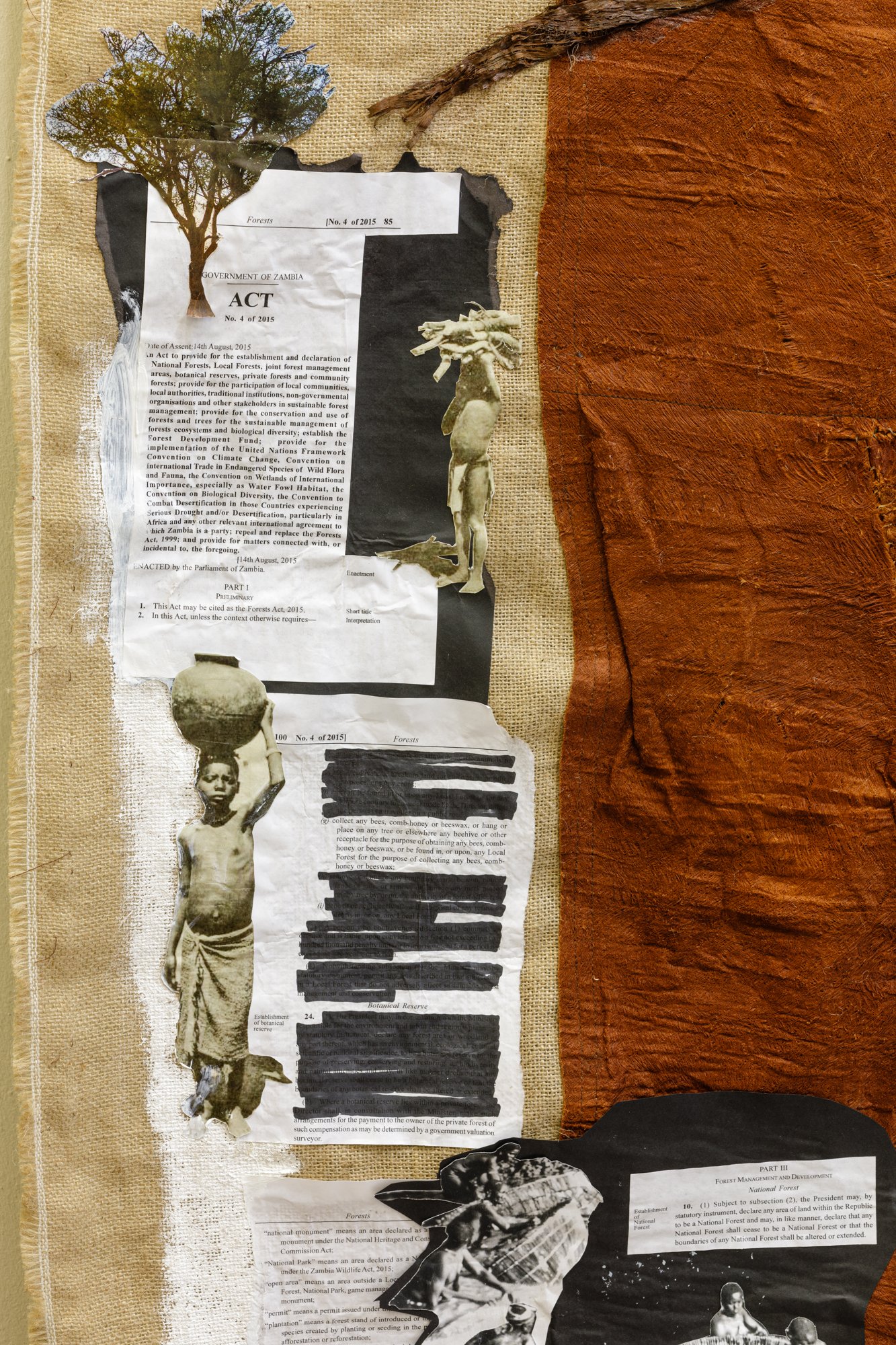

Isaac Kalambata’s collage work Mizyu (2025) seems to be a curatorial illustration of the impact of lawful immorality. Kalambata’s work showcases Zambian legislation on forests and property laws (No. 4 of 2025) with the word “DISPLACED” stamped in red on top of copies of the legislation, illustrating the ways in which the corrupt force of law has brought the displacement of Indigenous populations. The work is accompanied by photographs of what appear to be natives and their belongings. In the center of the piece, we see Mwendanjangula, the “Lord of the Forest,” with his hands tied behind him, eternally attached to a tree. The metaphor touches on the continuous battle between “development” in the eyes of the capitalist beholder and violence in the eyes of the subjugated. Mizyu draws inspiration from the Witchcraft Act of 1914, “a legislation that expressly sought to entrench the colonial Christian church by curtailing alternative spirituality and healing practices within what is now Zambia.” Colah, with the choice of this work, seems to criticize a porous distinction between “this is law” and “this ought to be law.”

Isaac Kalambata, Mizyu, 2025, detail, 13th Berlin Biennale, former courthouse on Lehrter Straße. Courtesy Isaac Kalambata. Image: Eberle & Eisfeld.

One question still lingers after seeing the thirteenth iteration of the Berlin Biennale: if justice is always contested, what are the standards on which it is based and can be counted on in civil societies? Colah’s curatorial approach persuades us to see law as malleable, contingent, and fugitive. TWAIL scholarship affirms this vision, as previously noted, by reframing justice as resistance, as an alternative horizon that refuses colonial hierarchies. In line with the critique that this approach can collapse into ambiguity, the late legal scholar Ronald Dworkin argued that law is always a matter of interpretation, with precedent neither rigid nor random. Yet it must offer integrity and moral validity. In the case of lawful violence, rejecting the law is acting in accordance with a deeper moral logic of the legal system. Essential to this is the discipline of principled interpretation; if everything is up for debate, integrity is lost and law dissolves into politics.9 Between these poles, Colah proposes that the fugitive fox that lives outside of the law, and whose figure suggests that law dissolves into politics, offers neither stability nor certainty. Instead, the fox is a provocation to reimagine the grounds on which justice stands.

Yet the Biennale stops short of articulating what, concretely, should replace that compromised ground. Fugitivity appears as the implied answer—an ethics of refusal, of moving beyond the law’s demand to be acknowledged—but it remains more mood than method. Indeed, the visitor is left with “a sense of a fox with its feet tied.”10 Part of this restraint may be structural rather than accidental: as a publicly funded platform, the Biennale cannot easily stage a critical political position without risking the charge of turning public culture into a partisan mandate.

Colah’s solution is to distribute judgment outward, where the viewers become the jury, and the exhibition provides tools rather than verdicts. But this redistribution produces its own problem. Advocacy requires a legible call and a transmissible ethics—something that can travel beyond the exhibition as more than ambiguity. If fugitivity is meant to be “passed on” as an activist ambition, the dramaturgical conceit promised by the Biennale demanded more than inference; it demands a legible call. Without clearer cues inside the exhibition’s curatorial script, the viewer is left to author the politics alone. In this sense, ambiguity functions as a protective condition. It is even possible that this suspension of principled interpretation was intentional. The Biennale’s reliance on ambiguity seems a wager for the consequences of advocacy to remain hidden, echoing the logic of the fox that survives by remaining elusive, but in doing so cannot be passed on.

Daniel Gustav Cramer, Fox & Coyote, 2024/25. Image: © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2025. Courtesy Sies + Höke, SpazioA, Vera Cortes, Yvon Lambert.

NOTES

1. Martin Herbert, “13th Berlin Biennale Review: What Doesn’t the Fox Say,” ArtReview, September 5, 2025, https://artreview.com/13th-berlin-biennale-for-contemporary-art-various-venues-berlin-review-martin-herbert/.

2. Andrea Scrima, “The Berlin Biennale’s Complicit Silence,” Hyperallergic, July 30, 2025, https://hyperallergic.com/berlin-biennale-complicit-silence/.

3. Colah’s iteration of the Berlin Biennale included four venues. The largest part of the exhibition took place at KW Institute for Contemporary Art. The other venues were the Hamburger Bahnhof–National Gallery for Contemporary Art, Sophiensæle, and the former courthouse on Lehrter Straße.

4. Zasha Colah and Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, eds., 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art: catalogue. (Berlin: Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, 2025).

5. Naz K. Modirzadeh, “‘Let Us All Agree to Die a Little:’ TWAIL’s Unfulfilled Promise,” Harvard International Law Journal 65, no. 1 (Winter 2024): 25–68.

6. John Simkin, “Karl Liebknecht,” Spartacus Educational, updated January 2020, https://spartacus-educational.com/GERliebknecht.htm.

7. Editor’s Note: In this regard, it is worth noting that when The New York Times asked President Donald Trump if there were any limits on his global powers, he replied: “Yeah, there is one thing. My own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me.” https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/08/us/politics/trump-interview-power-morality.html.

8. Simon Wachmuth, From Heaven High (2025). Wall label, 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, former courthouse on Lehrter Straße, Berlin.

9. Ronald Dworkin, Law’s Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986).

10. Herbert, “13th Berlin Biennale Review.”

-

Sophie Barfod is an independent curator from Amsterdam, the Netherlands. She works at the intersection of curating and strategy, currently contributing to W.A.G.E. and SaveArtSpace. Her practice is focused on curating in found spaces, with exhibition concepts often rooted in feminist theory and social practice work. She is currently a student in the MA Curatorial Practice program at the School of Visual Arts, with a Bachelor’s degree (honors) in Politics, Psychology, Law, and Economics from the University of Amsterdam. She has held positions at YAG (McKinsey partner), Heineken, Julietta Alvarez Galeria, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, and is an ex-founder of an experimental arts and technology startup in Amsterdam.